Here are no lying nor vain epitaphs.

– Henry David Thoreau

I blame a lot of things on my mother.

My high arches, baby fine hair, brown eyes and chocoholic tendencies are all traits I inherited from her. Along with her interest in cemeteries.

A dedicated amateur genealogist, Mom’s idea of small talk around the family dinner table when we were growing up was to relate recently verified facts of long-dead people in our family tree. But since her tales always lacked the reasons why John Reid married his first cousin Mabel after the death of his wife Jane sometime between the 1850 and 1860 census, I made up Mabel’s story.

Several years older than her cousin, Mabel wasn’t likely to win any prairie beauty pageants. But John Reid recognized that Cousin Mabel was a skilled seamstress who worked hard and had a talent for cooking, something Jane had decidedly lacked. And when John saw Mabel was willing to look after his motherless brood of five, it tipped the scales in her favor. Besides, how many unmarried women were wandering around Oklahoma Indian Territory at the time?

With these invented histories I connected with what I always considered a somewhat dubious ancestral line. And when Robie mentioned that our apartment in Liverpool was half a block from 30 acres of green, rolling hills at the Toxteth Cemetery, I knew there were compelling stories waiting to be discovered.

My first surprise was how many tombstones were written in foreign languages. In addition to a section of Welsh graves from nearby Wales, there were some in German, French, Danish and Greek reminding me that people from all points of the compass passed through this bustling seaport.

Among the headstones was Richard J. Fisher (died 1867) who hailed from Bermuda while William Dowling (died 1857) was a native of St. John, New Brunswick and Francis Louis Simond, Esq. came from Yverdon, Switzerland. Harold Johnstone (died 1926) traveled to the British Isles from half a world away in Sydney, New South Wales. And Grace Walsh (died 1859) arrived in Liverpool from the beautiful island of Dominica where she undoubtedly missed the Caribbean sunshine and tropical breeze of her homeland.

But people didn’t just come to Liverpool. Plenty of locals left the British Isles never to return. And though they’re buried elsewhere, they were remembered by friends and families at Toxteth.

William Henry Askwith died in 1891 in Melbourne, Australia. Annie Howe passed away at Crosse Isle, Quebec. Captain John Hawkins succumbed in San Francisco. William Cromarty perished in Guayaquil, Ecuador, John and Mary Carson in New Zealand. John Locke Parrett was laid to rest in Barbados, Arthur Bruce Cave in Bahia, Brazil and William, eldest son of George Parsonage in Trinidad. Samuel Dray Pierce was buried in West Africa. Joseph Andrew, youngest son of John and Elizabeth Jessup is in a cemetery in Pittson, Pennsylvania while Alfred Morgan (died 1888) can be found somewhere in Jacksonville, Florida.

Back then ocean voyages were notoriously perilous. George, eldest son of William and Susan Churchard died on passage from Rio de Janeiro in March 1860. George How, master mariner of Liverpool and his son George, Jr. were lost at sea while traveling home from Brazil. William Cockram lost his life in the collision between the Inman Steamer City of Brussels and the S.S. Kirby Hall on January 7, 1883.

Samuel Carr drowned on the barque Caletria. James Barry “fell from aloft” (the ship’s tall masts) before being buried at sea. Thomas Kidson drowned at sea, location unknown. Ann Ross and her two infant children died when The Royal Charter wrecked on the Welsh Coast in October 1859. And for the relatives of 19-year-old William Andrew, they only knew that their kinsman was presumed to have gone under with the Egremont Castle in 1879.

In an age when the captain always went down with his ship, there was no shortage of skippers commemorated at Toxteth Cemetery. Captain Henry Lewis drowned when Robin Hood sank in 1872. Captain Edward Clark died with his ship in 1874 as did Captain Henry Clark in 1909. Captain William Henry Thomas was lost at sea during Assaye’s voyage from Bombay in January 1864. And Captain Rowland Jones died when the S.S. Etolia sank on its homeward passage from India.

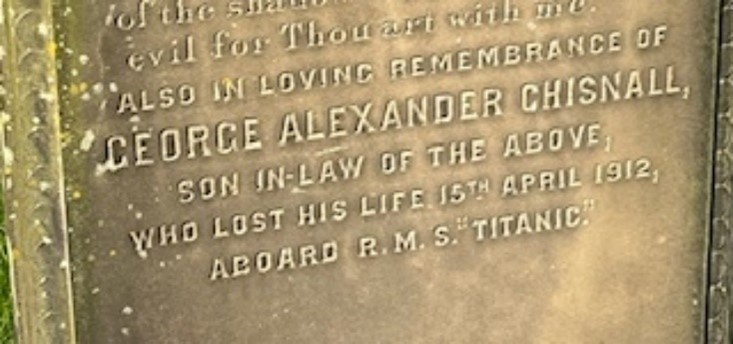

Then I found gravestones commemorating the two most famous shipping disasters of the 20th century.

Just behind Liverpool docks sits the two-toned brick building that was once headquarters for the White Star Line. And even though the Titanic never came to Liverpool, much of her crew hailed from Merseyside, the region surrounding the city.

Inside Liverpool’s Maritime Museum, Robie and I followed the dramatic final hours of local resident Captain Edward John Smith waiting on the bridge for a rescue that would never come. We read about Fred Clark who lived down the street from our apartment in Toxteth and played bass violin on deck with his band until the bitter end.

And we met members of the Titanic engineering crew.

On the night of April 14, 1912, George Alexander Chisnall was at his post as boilermaker when the massive ship struck the iceberg. For two hours Chisnall and his shipmates battled to keep the sinking ship afloat. Their efforts kept the doomed liner’s generators on and lights glistening in the black night allowing more lifeboats to be launched. And after every one of them lost their lives in the North Atlantic, they were memorialized in Liverpool’s Heroes of the Marine Engine Room.

But even though George Chisnall never lived in Liverpool, his widow Alice Hardy Day Chisnall moved to 2 Croxteth Grove with her young children following the tragedy and received £7.3 a month from the Titanic Relief Fund.

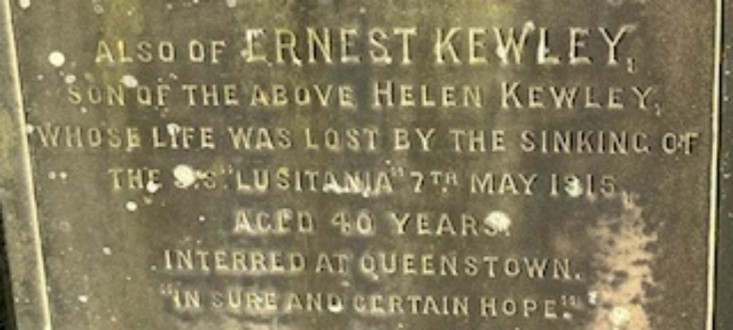

Three years later, Liverpool’s Ernest Kewley and Samuel Tyler, along with nearly 1,200 other passengers lost their lives when the British luxury liner Lusitania was struck by a German torpedo off the coast of Ireland during World War I. The U-boat attack, made without warning, fueled anti-German sentiments across the Atlantic and sent throngs of angry Brits to enlist in the war.

Not surprisingly, there are 274 Commonwealth graves in Toxteth Cemetery. Operating in more than 150 countries and territories, the Commonwealth War Grave Commission was established by Royal Charter at the end of World War I and works on behalf of the governments of Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the United Kingdom to care for the graves of the men (and at least one woman) who served in the two world wars.

Gladys Mary Jenks was a Leading Wren in the Women’s Royal Naval Service during World War I. A branch of the British Royal Navy, the Wrens freed up men for the front by working as military cooks and cleaners, clerks, communication operators, decoders, weather forecasters and captains of small vessels. And after the Wrens disbanded in 1919, when war broke out again, they reformed.

During World War II their duties expanded. Naval women were put to work locating mines, loading torpedoes, maintaining ships and plotting convoys across the North Atlantic for the Western Approaches command center. After the war, the Wrens remained an active branch of service until 1993 when women were allowed to join the Royal Navy.

Most Commonwealth graves at Toxteth are World War I veterans. Gunner D. Banks of the Royal Garrison Archery died October 1, 1914, aged 20. John Victor Calvey died at Gallipoli in November 1915, aged 17 years. John Richard Evans of the Welch Regiment was killed in France March 16, 1918, and interred in Cite Bonjean Military Cemetery Armentieres. Private Percival James Thomas of the 10th Liverpool Scottish attached to 7th Cameron Highlanders was killed in action at Ypres on July 25, 1917, aged 19 years. George Wallace Coats fell with the Liverpool Scotts June 16, 1915, at Hooge, Belgium. And despite the spontaneous Christmas truce that broke out along the trenches memorialized in a statue outside Liverpool’s bombed out St. Luke’s Church, Private J.W. Davies of the King’s Liverpool Regiment died 24th December 1914.

When Toxteth Cemetery opened in 1856 most of the city’s small church graveyards were closed from overcrowding. At the same time, Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famine were packed into tenement buildings without heat or indoor plumbing. Amid the squalor and unsanitary conditions of the Liverpool slums, infectious disease ran rampant.

One Irish immigrant, Catherine (Kitty) Wilkinson taught orphans to read and cooked for unwanted children despite her own meager means. During a cholera outbreak, Kitty turned her cellar into a laundry room and opened it to her neighbors to help combat the disease. When the epidemic finally subsided, Kitty pushed the city to create public bathhouses for the poor earning her the title “Saint of the Slums.”

Yet despite Kitty’s work, heartbreaking stories abound in Toxteth Cemetery. When James Harding lost his wife Letitia and newborn son he remarried, and together with Mary Harding he buried seven more infants. When Sarah Elizabeth Livesey died in 1876 she was preceded by seven of her children: George in 1860 (aged 1 year), Robert in 1861 (5 months), Catherine in 1865 (6 months), Frederice in 1870 (4 years) and twins Gertrude and Edith in 1874 (11 years). Fittingly, Sarah’s epitaph reads, “Her end is peace.”

But children weren’t the only casualties. A staggering number of women died in childbirth. Infections led to sepsis, skyrocketing blood pressure brought on seizures, postpartum hemorrhaging could be fatal and prolonged labor or retained placentas were death sentences. When Mary Wood died on October 2, 1864, she lasted two days longer than her infant son Charles Edwin.

After a woman died, she typically left a brood for her husband to raise. While many Toxteth markers list more than one wife for a man, remarrying wasn’t usually an option for many widows, and several headstones noted women passing within a few years of their husbands regardless of age. Sarah Margaret Potts, 47, died months after her husband Thomas Crosby Potts was laid to rest in July 1878 because without a pension, financial support or source of income, women too often succumbed to homelessness and starvation.

While many graves list the age of the deceased, few note their date of birth. But some include interesting details about their lives.

Before Josiah Cave died in November 1884 at the age of 56, he was a master mariner who lived at 42 Alderson Road across the street from the cemetery. Charles Chalk was a licensed victualler selling food to restaurants while Henry Richmond was a wine and spirits merchant. Charles Henry Vidal Collmer worked as a missionary in West Africa, Palestine and Lebanon. Westby Percival Eso was a justice of the peace in Knightsbrook County. Andrew Clement Baker worked for the Liverpool Mail and James Crow was employed in Her Majesty’s Customs while his brother John ran the family watchmaking business.

Bertram Fox was a commodore in the famous White Star Line, and Captain James Nicol Forbes commanded Marco Polo, the fastest ship in the world after he led her roundtrip between Liverpool and Australia in under six months.

Some tombstones detail the cause of death. Like Thomas, son of Richard and Sarah Worrall who was drowned in the Prince’s Dock while his brother John was killed by a fall in the hold of the ship Hannah Mary. Jonathan Cunliffe died from injuries he received while employed at Edge Hill Station on the London and Northwestern Rail and William H. John died while bathing in the Steble Street Baths. Tom Howden, beloved husband of Fanny, died in an accident in Shanghai, one of Liverpool’s most important trading partners leading to the establishment of Europe’s oldest Chinatown.

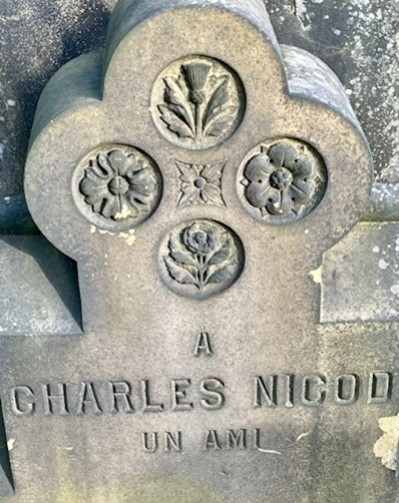

While some graves at Toxteth provide a lot of information, others are depressingly bare. For Frenchman Charles Nicod, his marker includes no date or age at death, no address or occupation. Instead, it states probably the only thing someone once knew about him, “To Charles Nicod, a friend.”

Stumbling across the headstone of Miss Mary Billinge, I discovered a local celebrity. At the time of her death on December 20, 1863, Mary was 112 years and 6 months. Because when you get that old, every half-year counts.

Finally, after our last post about Top 10 Cemeteries, my mother pointed out the omission of two very important cemeteries everyone should see: Cummings Cemetery in Pottawattamie County, Oklahoma and Lower Spring Creek Cemetery in Yell County, Arkansas where I apparently have ancestors from the Revolutionary War and Civil War.

So, here’s one last monument at Toxteth especially for me mum.

Partially hidden behind overgrown ivy lies a statue to James Dunwoody Bulloch, the chief foreign agent for the Confederate States of America in Britain. As a secret agent Bulloch helped Southern blockade runners sell cotton to English merchants and commissioned the sloop CSS Alabama to be built across the Mersey River from Liverpool. But as a spy Bulloch was left out of President Andrew Johnson’s general amnesty during Reconstruction and lived out his days as “an Englishman by choice.” His marker reads,

Strong ties of common ancestry existed between the Confederate States and the mother country, England. Warm ties of friendship developed between Bulloch and the English people. At the end of the war, he chose to remain in Liverpool. This inscription is dedicated with warmest appreciation and highest admiration to our mutual countryman.

-The United Daughters of the Confederacy, U.S.A. 1968.

Merry Christmas, Mom.