What is better than to sit at the end of the day and drink wine with friends, or substitutes for friends.

– James Joyce

Dublin is a literary town.

Bookstores, libraries, literary museums and tour, pubs where famous authors hung out, Dublin has them in spades. The city has contributed four Nobel laureates in literature and six Booker prize winners. It was a UNESCO City of Literature in 2010 and is home to a booming network of magazines, publishers and literary festivals.

In an interview with The Guardian in August 2024, Aisling Cunningham, owner of Ulysses Rare Books explained. “The Irish just chat about everything. We love telling tales and yarnin’. There’s no other country where you can talk for an hour about the weather.”

That was certainly the case when Robie and I visited Dublin.

At J.T. Pim’s, friendly locals chatted us up at the bar and by our table. And though we can’t say the one-sided conversations were about the persistent rain, Robie and I nodded and tried to laugh at the appropriate moments despite understanding little through the thick Irish brogues.

Fortunately for us, not all of Dublin’s stories needed words.

Inside Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, the life of the saint is reflected on three towering stained-glass windows depicting his early years in Roman Britain before a group of Irish raiders sacked his family’s estate and took sixteen-year-old Patrick to Ireland as a slave. After six years Patrick escaped, returning home to begin religious studies. And once ordained, he traveled back to Ireland and converted his pagan captors.

Surprisingly, Ireland’s national cathedral is neither Catholic nor the seat of a bishopric. The Irish Anglican church is overseen by a dean whose most famous leader was Jonathan Swift.

A clergyman by trade, Swift would have preferred a career in politics. But in the ongoing struggle between Protestants and Catholics in 18th century Europe, religion was politics. And when he wrote Gulliver’s Travels, Swift depicted his protagonist’s misadventures as a political satire (tightrope walking Lilliputians balancing power and politics), poked ecclesiastical fun at science (giant Brobdingnagians appearing like something under the recently invented microscope), mocked the public’s trust in technology (harvesting sunbeams from cucumbers) and lampooned the glut of fanciful travel narratives popular at the time.

But while it seemed strange for an author of fiction to be at the heart of the Irish church, Dublin’s literati often found inspiration in their hometown.

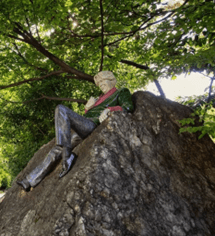

Prior to writing The Picture of Dorian Gray, a young Oscar Wilde pondered the meaning of beauty at his job in a grocery store attached to Kennedy’s Pub & Restaurant, a favorite haunt of Samuel Becket who, like his characters in Waiting for Godot, frequently lingered while a teenage James Joyce served as parttime barman.

In Dracula, Bram Stoker evoked images from his job at Dublin Castle. And when James Joyce portrayed Dublin’s streets and characters in Ulysses and Dubliners, he recalled memories of The Lincoln’s Inn, a spot Robie and I ducked into for Irish stew and steak and Guinness pie.

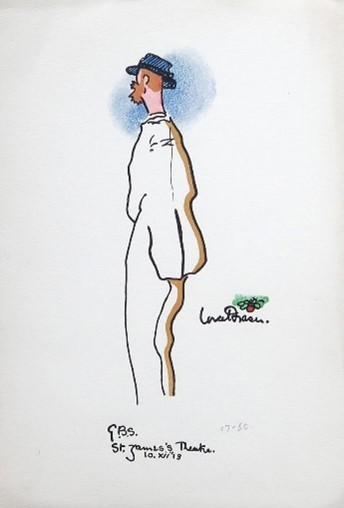

During an afternoon at the National Gallery of Ireland, Robie and I were surrounded by the works of Caravaggio, Degas, Rembrandt, Velazquez, Monet and Picasso. And the museum was the scene where playwright George Bernard Shaw once claimed he owed “much of the only real education I ever got as a boy in Eire.”

Nursing pints in one of Dublin’s oldest pubs, we discovered the stomping grounds of the Fenian Brotherhood, a secret organization that fought for Irish Independence.

Opened in 1766, under The Long Hall’s Victorian décor, members of the brotherhood planned the failed Fenian Uprising of 1867, a precursor to the Easter Rising that though quickly suppressed, paved the way for Irish independence after one of its leaders, James Connolly, was imprisoned in Dublin Castle and executed for his role in the rebellion.

With more pubs than cafes in Dublin, when Robie and I wanted something besides Starbuck’s, we sat down amid the French memorabilia and Parisian joie de vivre at Le Petit Perroquet sipping café au laits and munching buttery croissants. Because even Dublin’s new establishments have stories to tell.

Despite the city’s catalogue of tomes, authors and plays, its most famous manuscript is the Book of Kells. And for €50 Robie and I could see two beautifully illustrated, highly decorated, dimly lit pages from the New Testament Gospels alongside fifty other tourists elbowing for a peek before being herded into the Trinity College Library where all but the lower shelves have been emptied to preserve the books for future generations.

After reading disappointing reviews detailing the crowds, limited visibility and largely empty library, when some insightful person called the Book of Kells Experience the Mona Lisa of Dublin, “small, hard to see, and not worth trying to get through the hordes to view it,” Robie and I skipped it and planned a visit the Chester Beatty library instead.

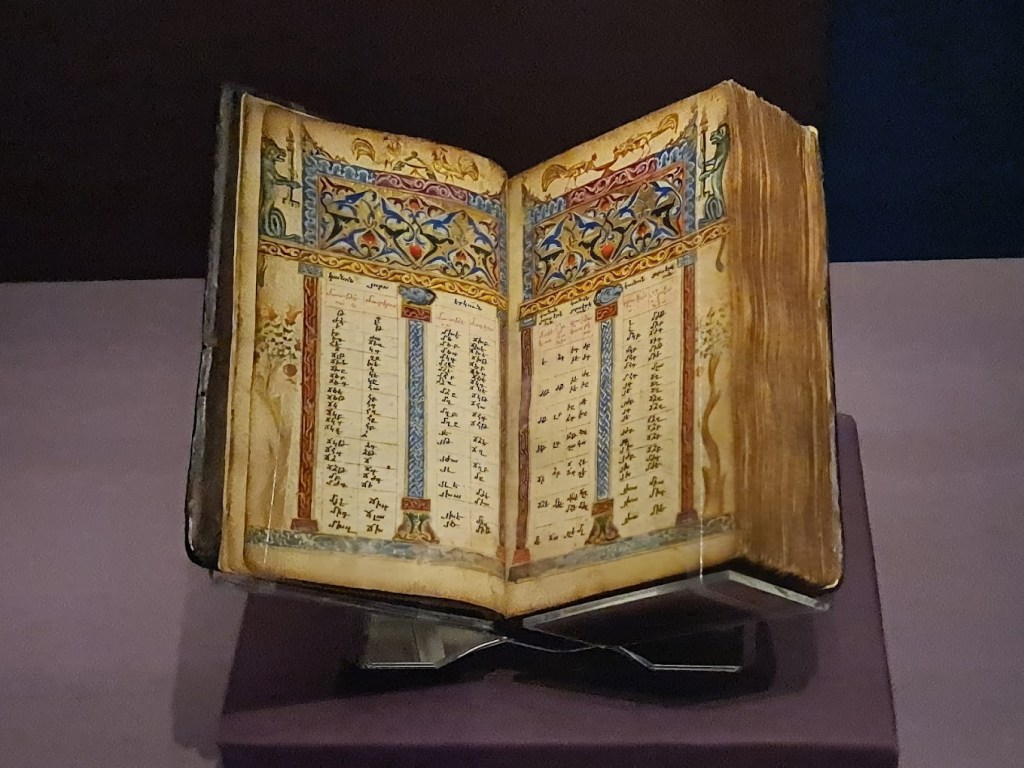

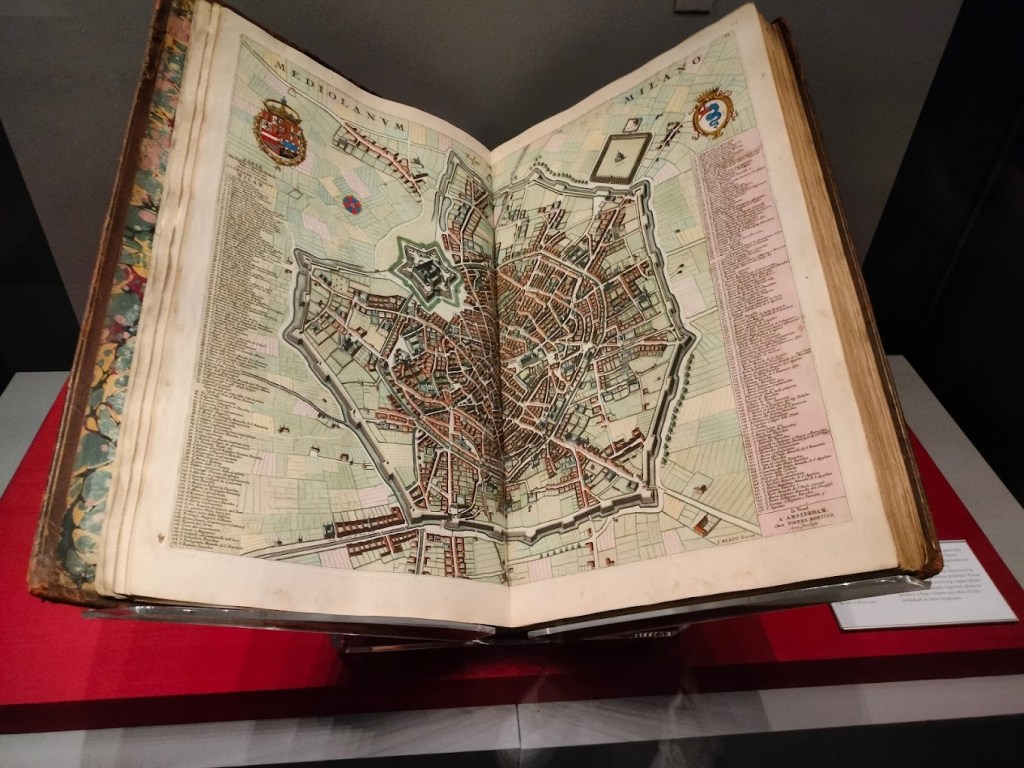

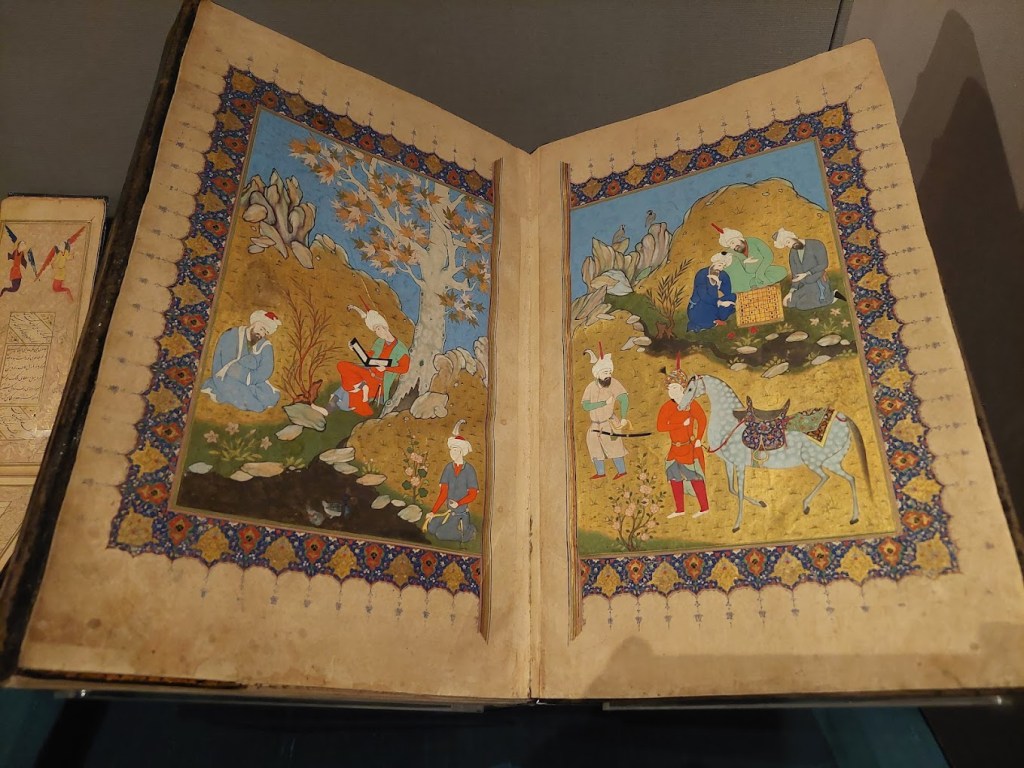

Books from the Chester Beatty Library

American mining magnate Chester Beatty spent his fortune amassing rare manuscripts featuring hand painted, elaborately ornamented, beautifully bound books from China, Japan, India, Tibet, the Middle East and Europe. In the Far East he acquired albums painted with complex battle scenes and scrolls of exquisite calligraphy. In Cairo he collected Egyptian papyri and Hebrew texts. Across Asia he compiled Quranic writings in Arabic and Persian from the Ottoman Empire to Moghul India.

In 1931, Beatty acquired eleven Greek passages from the Old and New Testaments written in the 3rd century, an astonishing discovery that proved a Greek Bible survived Christian persecution by the Romans and pushed Biblical scholarship back a century. So, it’s a shame more people don’t visit the library across the gardens from Dublin Castle. Because not only does the collection rival the religious significance of the Book of Kells at Trinity College, it’s also free.

With so many rich stories to uncover in Dublin, our favorite began when a friend told Robie about a Michelin-rated pizza joint. Because one of the downsides to our Friday night tradition is that we rarely order pizza out – unless of course, we’re in Italy.

But Dublin isn’t Naples. Or Rome. So, what was so special about the pies at Little Pyg Restaurant that they caught the eye of the famed restaurant guide?

Interior of Powerscourt Townhouse Center

In the middle of Powerscourt Townhouse Center’s atrium beneath a glass canopy surrounded by tall green plants, Little Pyg is a tropical oasis in the heart of Dublin offering Neapolitan pies topped with simple, delicious flavors.

Opting for a burrata salad with cherry tomatoes, basil pesto and Parma ham served with puffs of soft fried dough, Robie and I sopped up the tasty combination. Then we cut into a pizza made with San Marzano tomatoes, spicy Calabrian meatballs, gorgonzola and parmesan cheeses drizzled with sweet honey and extra virgin olive oil.

Our server explained the story of Little Pyg. After opening in November 2019, the restaurant quickly closed again due to Covid lockdowns. But after owner Paul McGlade brought in bricks specially made from rocks around Mount Vesuvius along with 14 Italian workmen to build Little Pyg’s custom-made pizza oven, he wasn’t planning to stay closed. And not after he sent his chefs to Naples on 3-month internships with fourth generation pizzaiolo, Maestro Enzo Coccia, the man whose restaurant, La Notizia, was the first pizzeria recognized by Michelin.

Coccia, co-founder of Pizza Consulting now teaches the art of making pizza according to rigorous Neapolitan standards and time-honored traditions. After returning from Litte Pyg’s grand opening in 2019, Coccia explained his philosophy to a Pizza University class. “It is a calling that is passed down from father to son for generations. That is how it happened to me. My father was a pizzaiolo, I became one, and now I am teaching the profession to my children.

“This,” says the Maestro, “is a very important aspect: the family tradition, the passing down of knowledge and know how that was as present in Naples yesterday as it is today.” Which is why in 2017, Neapolitan pizzaiolos were recognized by UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

For Little Pyg, the investment and training paid off.

In May 2024, the restaurant placed 15th at the Pizza Europa Awards in Barcelona. Then, two weeks before Robie and I ate there, Little Pyg made history again at “The Worlds,” the prestigious World Pizza Awards where the restaurant was named Ireland’s No. 1 pizzeria and earned a spot in the Top 100 Pizzerias in the World.

And after devouring our delicious Little Pyg pie, we considered that a story worth telling.

Planning a trip to Dublin? We’ve included links to the places we visited. If you’ve already been, we’d love to hear about your favorite spots. Send us a note or leave a comment below.