It takes a lifetime for someone to discover Greece, but it only takes an instant to fall in love with her.

– Henry Miller

Robie and I didn’t want to go back to Santorini.

The place held too many memories. Like cruising around the caldera on a catamaran cruise and riding the rugged cliffs in a rented scooter. Ordering calamari from a seaside taverna and watching the chef slice a squid he got from a boat tied up in front of the restaurant. The hearty congratulations of the town’s mayor and our parade through Oia to strolling musicians and firecrackers.

In the three decades since, Santorini’s been ranked the world’s top island by US News, Travel + Leisure and BBC, to name but a few. In 2024 the island welcomed 3.4 million tourists as 17,000 cruise ship passengers disembarked on the island each day in July and August to get a glimpse of the whitewashed buildings, blue-domed roofs, dramatic cliffs and breathtaking sunsets.

Robie and I worried a return to the island couldn’t live up to our memories, so on our new adventure we chose an obscure Greek island few people had heard about or knew how to pronounce. Including us.

When Robie found the beautiful one-bedroom apartment above a restaurant with views of the Mediterranean, he thought the place might be too quiet. But while I traveled around the country for work and he got the house ready to sell, peaceful, tranquil and remote sounded perfect.

Named after the mythical kid who flew too close to the sun and melted the wax in his wings, Ikaria (pronounced ick-car-EE-ya) is the place Icarus’ body washed ashore after plunging to his death.

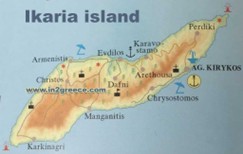

Its location in the eastern Mediterranean makes Ikaria closer to Istanbul than Athens while rough seas and annual winds known as meltemi make for some of the most treacherous waters in the Aegean. Shaped like a slanted tilde, the island’s unbroken coastline and bleak, rocky landscape led Englishman Charles Perry to describe it as “the most miserable, barren rock that ever was seen” after he took shelter on Ikaria in a storm.

For much of its history, Ikaria has been overlooked, bypassed and forgotten. While Alexander the Great built the Tower of Drakano for defense and an observation post, Rome noted the natural hot springs. Under the Byzantines, Ikaria was a place of exile for members of the royal family, and despite centuries under distant governments in Venice, Genoa and the Knights of St. John, no foreign culture had any lasting impact on Ikaria.

In antiquity the Aegean was plagued by pirates. The Amarna Letters mention “Lukkan pirates” raiding the Mediterranean in 1350 BC and a monument of Rameses III describes naval attacks against “sea peoples” (pirates) from Crete and Anatolia. In 75 BC, Cilician pirates kidnapped Julius Caesar and held him for ransom on Pharmacusa, today’s Farmakonisi in the South Aegean. And during the 1,100 years of the Byzantine Empire, Barbary corsairs roamed the coasts unchecked.

Determined to thwart the pirates, Ikarians destroyed their ports. But when sabotage proved ineffective, they withdrew into the island’s rugged interior.

Since Roman times the islanders had found temporary refuge in their mountains. Only now they moved inland and constructed sturdy stone houses covered with slate roofs that blended into the rocky terrain. They hid in windowless houses made without chimneys so billowing smoke wouldn’t alert passing ships. They planted fruit trees and tended to small herds of goats and sheep, cultivated gardens, raised chickens and learned to forage for food. And during a “century of obscurity” they tried to convince outsiders the island was deserted by sleeping during the day and venturing out only after dusk.

With the fall of the Byzantine empire, Ikaria came under Ottoman rule. But when Ikarians saw the Ottoman Empire was being bled dry by rebellions in the Balkans and a costly war with Italy, they marched against the island’s small garrison and established the Free State of Ikaria.

Cut off from its neighbors, without money or resources, the newly independent state applied to Greece for support. And once the First Balkan War began, Ikaria was absorbed into Greece once again.

In the waning days of World War II, Greece erupted into civil war as communists and resistance fighters fought for control of the country. But after Churchill and Stalin agreed to a Soviet-controlled Romania in exchange for a British-controlled Greece, the war quickly ended.

In the aftermath of the civil war, 10,000 communists were exiled on Ikaria. As an island with no natural harbors and hazardous meltemi winds, Ikaria had been a prison for dissidents since Roman times and a place of “administrative banishment” as late as the 1920s. And once it became known as the ‘Red Rock,’ it was once again ignored.

For centuries Ikarians had lived without significant state oversight building a self-reliant society based on community, hospitality, sharing and reciprocity. So, without aid from the Greek government, they employed their traditions and welcomed their new neighbors sharing food and clothing and giving them abandoned homes to live in.

Neglected by Athens, progress came slowly to Ikaria where footpaths through the mountains were the highways and people walked until roads were constructed in the 1990s. And today the island’s a quieter, sleepier version of its famous neighbors, Mykonos and Santorini.

On Ikaria every villager still maintains his own garden and orchard. Many raise sheep and goats, harvest their own olives, cultivate honeybees, make wine, cheese and yogurt. And nearly everyone fishes and forages for mushrooms, figs, berries and wild herbs.

On the island food is prepared simply with seasonal ingredients. In spring they eat wild apricots and figs and dry the excess in the sun to hold them through the winter. In fall, they turn their bounty of summer produce into Soufiko, a vegetable stew similar to ratatouille. All year they enjoy wild greens filled with antioxidants, local honey with high antibacterial properties and fish rich in omega-fatty acids. They drink tea steeped in wild herbs and consume wine made without additives.

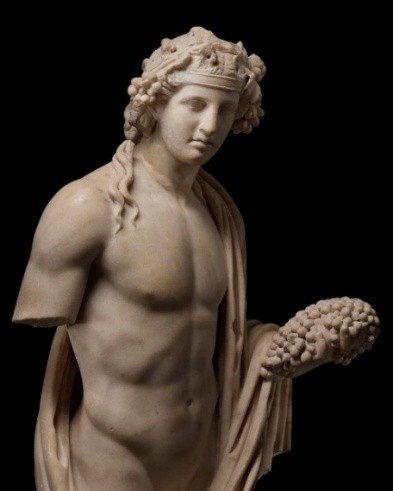

Ikaria is the mythical birthplace of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, and on the island people continue to make it by harvesting the grapes according to a lunar cycle, crushed by foot and left to ferment in clay pots underground, a process little changed since ancient times. Even Homer mentions Ikarian Pramnian wine giving Greek warriors strength and casting the spell on Odysseus’ men that turned them into pigs.

Arriving on Ikaria, Robie and I fell easily into island life. We slept late and lingered for hours over small cups of strong Greek coffee. We hiked and swam, spent time in the therapeutic baths and ate fresh fish and vegetables. We enjoyed leisurely lunches, napped in the afternoon and drank wine with friends in the evening. We attended Greek Orthodox services, went to an all-night panagiria dance party, got adopted by a local cat, and contributed to a boys’ basketball team raising money for an off-island tournament.

Because on Ikaria, life was slow, easy, good. Just the way it should be.