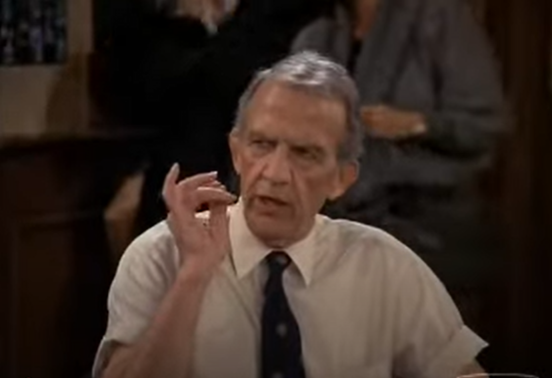

Albania, Albania, you border on the Adriatic.

– Coach in Cheers

When we told my parents we were headed to Albania, my mom had to use an atlas to figure out where it was. So for anyone else who only knows the country from the Cheers song played to the tune of “When the saints go marching in,” here’s a short primer.

Surrounded by Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo and Montenegro, Albania sits on the Adriatic Riveria across the sea from Puglia in southern Italy. Located near the crossroads of Asia and Europe, tiny, mountainous Albania often came under the control of powerful neighbors.

Alexander the Great battled indigenous tribes in Albania learning mountain warfare that he later employed in campaigns across Persia. After fighting three wars, Rome finally conquered the land they called Illyria but when the Empire split Albania fell under Byzantine rule. And when the Ottomans overran Constantinople, Albania and the rest of the Balkans provided them a toehold in Europe.

As Balkan nationalism simmered setting the stage for World War I, Albania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. But in a mountainous country where travel was limited, divisions ran deep. Ethnic Greeks set up headquarters in the south while France, Britain and Germany selected Prussian Prince Wilhelm of Wied to serve as Albania’s king making his capital in the north. In between lay the predominantly pro-Ottoman peasants.

As war broke out across Europe, Albanians revolted along religious and tribal lines. And once Prince Wilhelm fled, Greece attacked from the south while Serbia and Montenegro claimed parts of the north and Italy occupied the rest.

To lure Italy into the war on the side of the Triple Entente, Russia, France and Great Britain secretly agreed to carve up Albania. But during the Paris Peace Conference U.S. President Woodrow Wilson blocked the clandestine alliance and fought for Albania’s right to self-determination, an act Albania repays today in granting Americans the right to stay in the country for a year without a visa.

After the devastating war, Albania struggled to survive. Greece and Serbia continued to covet parts of the country while Italy manipulated local politics. But when the government set out to abolish feudalism, invest in infrastructure and enhance education and healthcare, it turned to the only country willing to lend it aid, the new communist regime in the Soviet Union, an undertaking seen by many as too dangerous to allow.

Heavily influenced by Italy, foreign powers installed exiled former prime minister Ahmed Zog as president, and he soon proclaimed himself Zog I, King of the Albanians. Then despite Italy’s longstanding backing, Mussolini invaded seeking to elevate Italian prestige after Hitler annexed Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia. And when Mussolini’s fascist government collapsed, Germany occupied Albania.

A year into Nazi occupation, partisans liberated Albania and set up a government that embraced Marxist-Leninism. Under the 40-year autocratic regime of Enver Hoxha, travel was restricted, private property abolished, and the world’s first atheist regime established.

Albania’s location at the crossroads of history also put it in the intersection of three major religions. As early Christianity spread, Catholic communities took root in Albania. But in the Great Schism, the country fell under the sphere of the Eastern Orthodox Church. And when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople, they introduced Islam to Albania.

For centuries Albanians of different faiths coexisted peacefully. Before World War II, Albania was one of the few European countries providing visas to Jews through its Berlin embassy as Muslim and Christian Albanians helped German Jews avoid arrest by providing false papers. But under Enver Hoxha all religion was banned. Church property was nationalized, clergy from every faith were publicly executed, and propaganda depicted clerics as backwards or agents of the West.

During the Cold War Albania’s relationship with the Soviets deteriorated, and in 1961 Albania withdrew from the Warsaw Pact siding with China in the Sino-Soviet conflict. But when Albania’s ties with Communist China cooled, the country was completely isolated. Fearing invasions by Yugoslavia, Greece, NATO or the Soviet Union, Hoxha ordered as many as 750,000 concrete bunkers erected across the country, a vast building project that’s still visible across the landscape.

In 1992, Albania became the last of the Soviet satellites in Europe to throw off communism. Five years later, the country came close to civil war when lax regulations and profound financial illiteracy of the people led to a series of pyramid schemes that gripped the country. When these programs – mainly fronts for money laundering and arms trafficking – could no longer make payments, Albanians erupted in demonstrations. As foreign embassies evacuated their people and the government collapsed, one in six people in the largely agrarian country lost their livestock and their homes to the tune of $1.2 billion.

Three decades after the fall of communism, the transition to capitalism is still a work in progress. While the nouveau riche strut along Sarandё’s promenade in expensive Nikes and the latest Italian fashion, shepherds in the hills live as their grandparents did, tending gardens and driving their herds to pasture.

But the most visible change is the city skyline where new buildings pop up like daisies in springtime and the constant hum of construction equipment adds more hotels and apartments for the tourists flocking to Albania. Because with miles of pristine coastline, four UNESCO World Heritage sites, stunning Albanian Alps and Europe’s oldest lake, tourism is booming in Albania.