The air soft as that of Seville in April, and so fragrant that it was delicious to breathe in.

– Christopher Columbus

At the end of the 15th century Seville was already known for its rich culture and dynamic history. Located 55 miles up the Guadalquivir River from the Atlantic, Seville was founded by Rome, turned into a center of learning under the Moors and the site of a deadly but effective siege by Christians during the Reconquest. Three years into the 16th century, the small city in southern Spain emerged as the center of the world.

A decade after Columbus’ first voyage, the Spanish crown granted Seville exclusive rights to trade with the Americas. This monopoly to oversee goods and people traveling between Spain and her colonies fed the city’s economy as galleons lined up to unload spices from the Far East, gold from Peru, emeralds from Colombia and silver from Mexico. As Seville became Europe’s richest, most populous city, it drew merchants, investors and artists creating a vibrant, cosmopolitan center.

While today’s visitors spend time wandering the world’s largest Gothic cathedral and exploring the breathtaking mix of architecture at the Real Alcázar (Royal Palace), on a recent visit Robie and I set out to uncover Seville’s Golden Age.

Here’s what we found.

Archivo General Museo de Indias

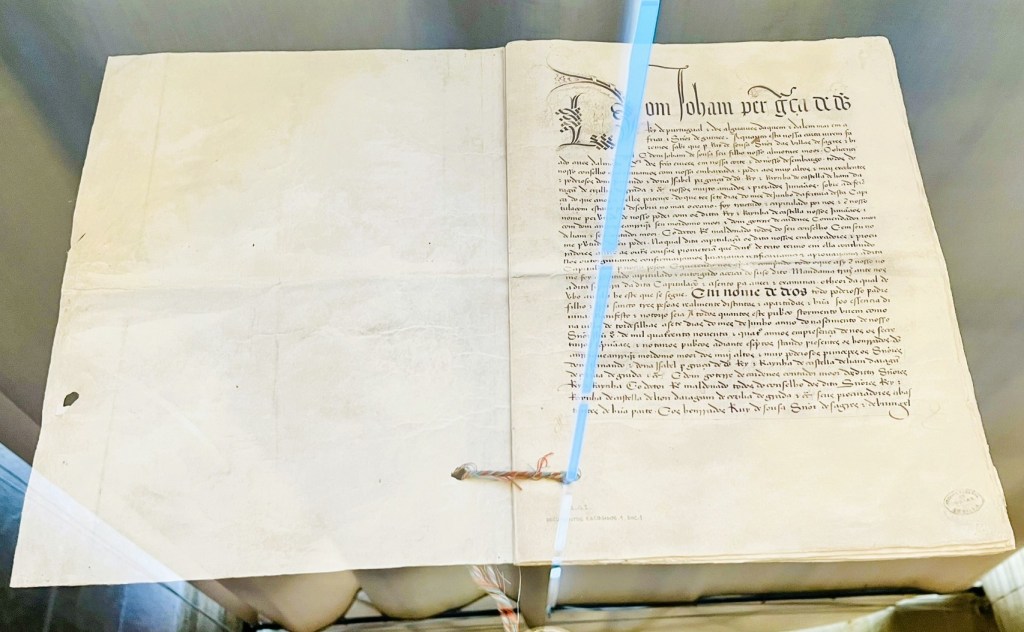

Established in 1777 by King Carlos III, the Archive of the Indies contains more than 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of bookshelves filled with 80 million pages documenting four centuries of colonial history in the New World.

The massive collection includes photographs, drawings, letters, maps, administrative records and diaries regarding Spain’s American territories. Within these halls are details of colonial life from explorations and discoveries to trade, slavery, religion, mineral findings, military operations, Indian relations and cultures. Amid the faded, brittle pages are transcripts of Columbus’ journal, letters from Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro and Juan Sebastián Elcano, thousands of maps and plans of colonial cities, routes and territories, even a job application from Miguel de Cervantes (author of Don Quixote) and several Goya paintings.

There’s an original copy of the Treaty of Tordesillas, the settlement between Spain and Portugal amending a papal bull and dividing the globe between the two Catholic countries as well as a cannon from the Atocha, a Spanish galleon that sank during a hurricane off the Florida Keys carrying an immense cache of gold, silver and emeralds famously discovered by treasure hunter Mel Fisher in 1985.

The archives are housed in the elegant Renaissance House of Trade, the building that once managed Spain’s monopoly with its colonies and controlled everything from licensing ships, collecting taxes and regulating trade to creating maps and organizing convoys.

The Nao Victoria

Bobbing along Seville’s waterfront is the meticulously crafted, full-size replica of the Nao Victoria, the first ship to circumnavigate the globe. And in the nearby museum we learned the ship’s storied history.

Following Columbus’ final voyage it was apparent that the Americas weren’t part of Asia but a separate continent. The papal bull creating an imaginary line in the Atlantic dividing the planet between Spain and Portugal and amended in the Treaty of Tordesillas, granted all lands east of 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands to Portugal. Sponsored by Prince Henry the Navigator, Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama sailed around Africa and became the first European to reach India by sea. Desperate to counter Portugal’s growing dominance in Asia, Spain hired Ferdinand Magellan to find an alternate route to the Far East.

On September 20, 1519, Magellan and a crew of 270 men set out with five ships to sail west into the Atlantic, locate, traverse and name the strait at the tip of South America and travel across the Pacific to the Spice Islands in present-day Indonesia. During the two years it took to reach the islands the crew endured sabotage, starvation, storms, scurvy and hostile natives.

Of the five ships, one was wrecked off the coast of Argentina during a storm, one mutinied and returned to Spain, one was scuttled in the Philippines when there wasn’t enough crew left to man her, and one attempted to reach Spain by crossing the Pacific again. It failed. Only the Nao Victoria survived.

Laden with a valuable load of cloves and cinnamon, the Nao Victoria headed west into Portuguese waters. After Magellan’s death in the Philippines, the ship came under the command of Basque sailor Juan Sebastián Elcano who dared to cross into hostile territory. Battling storms and inadequate supplies, the crew navigated their way across the Indian Ocean losing twenty men to starvation before reaching the Cape of Good Hope.

Turning north they sailed along the coast of Africa occasionally stopping for provisions while constantly pumping to keep the badly leaking Nao Victoria afloat. Reaching the Portuguese-held Cape Verde Islands, Elcano’s crew were exhausted and starving. Risking everything to resupply his ship, Elcano claimed the Spanish Nao Victoria had been blown off course during a storm in the Caribbean.

When Portuguese officials became suspicious, they captured thirteen members of the Nao Victoria crew and discovered that the ship had violated the Treaty of Tordesillas. Enraged, they demanded Elcano surrender the Nao Victoria with its precious cargo.

Elcano fled Cape Verde with a skeleton crew and evaded Portuguese pursuit in the open Atlantic. On September 6, 1522, nearly three years after leaving Spain, Elcano and seventeen emaciated men landed at Sanlúcar de Barrameda on their way to Seville marking one of the greatest achievements in the age of exploration.

The voyage of the Nao Victoria provided empirical data that the Earth was a sphere, found a vital passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and revealed the Pacific was much larger than expected. Most important, the spices Elcano brought back to Seville more than covered the cost of the original five-ship expedition fueling further explorations.

Palacio de las Dueñas

With gold, silver and spices pouring into Seville from around the globe, wealthy Sevillanas erected palatial homes.

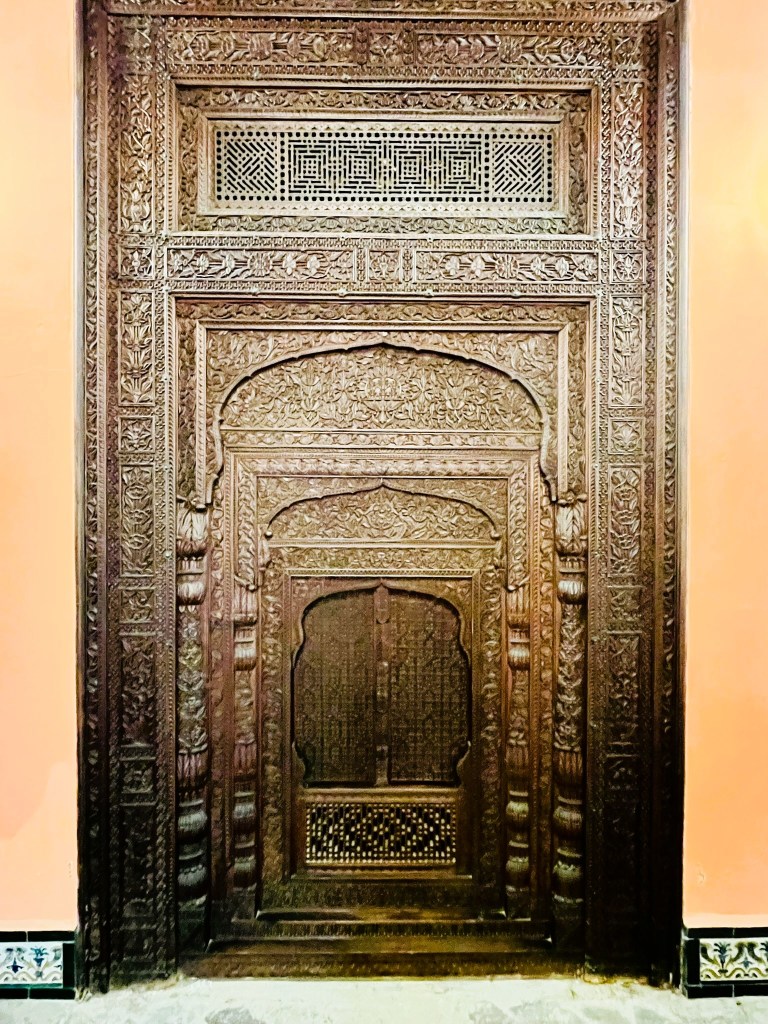

Built during the 15th and 16th centuries, the Palacio de las Dueñas blends Gothic, Mudejar and Renaissance styles with horseshoe arches, ornate ceilings and doorways, intricate tilework and more than a hundred marble columns. Designed to provide airflow and shade during hot Spanish summers, the traditional central courtyard with surrounding gardens were key elements in Sevillana homes and filled with vibrant colors, fragrant flowers and the sound of water.

Growing up in the Palacio de las Dueñas where his father served as caretaker, Spanish playwright and poet Antonio Machado captured the essence of the palace when he wrote, “in my childhood are memories of a courtyard in Seville” evoking sensory recollections filled with color and the scent of lemons.

Today the Palacio de las Dueñas houses a significant art collection that includes antiques and artifacts as well as Ribera’s Christ Crowned with Thorns and a pen and ink drawing in a guestbook signed by Salvador Dalí.

Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla

Backed by the immense wealth coming from their global empire Seville’s nouveau riche adorned their churches and homes with art.

In the 16th and 17th centuries two schools of art thrived in Spain. In the capital, paintings centered around courtly life where masters like Diego Velázquez and Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo created regal portraits of King Felipe IV and his daughter, the Infanta Margarita Teresa. In Seville, art was about prestige and piety.

The Sevillana school of art combined a Baroque style with dramatic realism, religious virtue and a mastery of light and shadow. Focusing on emotion and grandeur, the Catholic Church commissioned works for cathedrals like Seville that reaffirmed its doctrine and countered the Protestant Reformation. Emphasizing religious narratives that inspired devotion, the Seville school produced works now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts like Murillo’s stunning Immaculate Conception (La Colosal) and Zurbarán’s monumental work showcasing his skill as “the Spanish Caravaggio” in St. Hugh in the Refectory along with portraits of important people in Seville society by El Greco, Goya and Velázquez.

Like the Medici in Florence who sparked the Renaissance with their vast fortune, Seville’s increasing wealth fostered a flourishing art scene.

While the city had rivals in Lisbon, Venice and Beijing during the 16th century, for a time Seville’s maritime power, global reach, trade networks, burgeoning population and cultural influence made it the center of the world.