A little imagination goes a long way in Fez.

– Tahir Shah

Authors’ note: This post follows Reid’s travels in Morocco during college. The country, so vivid and exotic was unlike any she’d seen before. Mesmerized, she vowed to return but it would take nearly four decades before she rediscovered this wonderful country.

Before delving into our current Moroccan travels, we wanted to share what captivated Reid then and drew us here now. Read on to experience the sights, sounds and smells of the Gateway to Africa.

-Reid & Robie

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A cacophony of scents assaults my nose.

Trailing a perfume of warm flour and yeast, a young boy dashes around us balancing a tray of freshly baked loaves on his head. The enticing aroma is quickly overpowered by the musty fragrance of dried wool from hides piled across a donkey’s back, a sour odor that mixes with the earthy smell of the animal’s droppings.

Walking through clouds of peppery paprika, nutty cumin and woodsy cloves, my nose is cleansed by a bouquet of citrus. The waft of freshly squeezed oranges allows me to catch hints of lavender, mint and jasmine rising from the mounds of loose teas until their subtle scents are drowned out by the bitter whiff of hashish emanating from a darkened doorway.

The din in my nose is mirrored by the noise in my ears. An artisan’s tinny hammer chinks against a small brass plate rhythmically keeping time with the clomp of the ass’s hooves hitting wet cobblestones. Screaming children run between the legs of men and donkeys as live chickens dangle from wooden rods squawking pathetically. Arabic voices beckon us from the stalls while above the roar comes the wail of the imam calling the faithful to prayer.

I’ve come to Morocco on a weekend trip from college. Though not included in our study abroad program, Morocco sits so tantalizingly close to Spain that my roommate and I begin planning a trip our first week in Salamanca. After hopping a network of trains across the peninsula, we boarded a ferry to Tangier where Africa greeted us in darkness and chaos.

Throngs of people barked and waved shouting to become our guides. The only people not trying to get our attention was a gang of boys looking for their next pickpocket. As we navigated our way carefully through the crowd, Carolyn and I stopped when a shouting match broke out between a licensed tour professional and eager student over who saw us first. With the argument drawing the attention of the mob, we used the distraction to make our escape.

Running to the station, we boarded the next train to Fez.

The next day we passed beneath the intricately carved archway and entered the Fez medina following Sayed. Pausing to let our eyes adjust to the dim light, the Tangier university student explained, “No bicycles or motor vehicles are allowed here. Only pedestrians and medina taxis.”

“What are medina taxis?” Carolyn asked.

“Donkeys. They transport everything in the old city. Food, merchandise, clothes and people.”

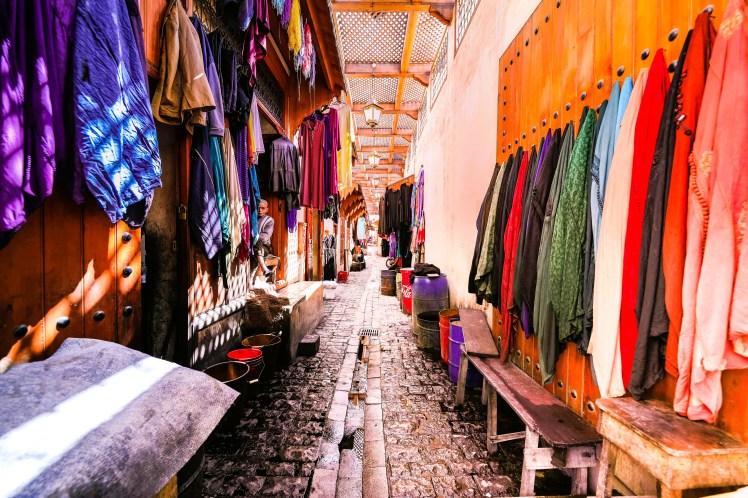

Climbing a slight rise, we turned sharply and descended into the abyss emerging in an alleyway where hundreds of stalls with colorful awnings provide cool shade from the pockets of intense sunlight dotting the stone floor. As Sayed leads, Carolyn and I cock our heads gawking at intricate lace veils, leather shoes, bronze housewares, handbags, colorful silk scarves and handmade clothes next to factory-made Western style t-shirts. When I look up again, I see Sayed twenty yards down the passageway. Grabbing my roommate’s elbow, I propel her forward. “We have to keep up.”

Afraid of losing our guide in the labyrinth where my sense of direction is upended, not for the first time I wonder what we really know about the man we’re following.

We met Sayed on the train to Fez. Overcrowded and delayed, when the railcars finally reached the end of the line it was nearing midnight. As haunting images of Tangier’s port returned, Carolyn and I accepted Sayed’s offer to escort us to a hotel. Then late this morning he returned to take us on a tour of his hometown. But as we follow him through the ancient fortification designed to confuse and entrap an invading army in weblike streets my stomach tightens knowing we have little chance of finding the way out, our only option to trail the mysterious stranger.

For half an hour Sayed steers us deeper into the maze. As we come down a narrow alley, our guide ushers us through a door. Inside, Carolyn and I find ourselves inside a small anteroom filled with thick rugs and an old sofa facing a sun-drenched courtyard. Closing the door, Sayed removes his shoes, and my roommate and I quickly follow.

Across the patio, a middle-aged woman wearing colorful robes glides across the courtyard. “Allow me to present my mother,” Sayed says proudly as the woman reaches her hands to Carolyn’s face and kisses both cheeks before turning to me for the same treatment. Behind the flowing dress, a girl emerges whom Sayed introduces as is his baby sister Fatima. At the sound of her name, the girl lowers her eyes and bows slightly. Then Sayed’s mom waves her hands and issues a series of instructions in short, commanding tones as she and Fatima disappear again across the patio.

“Sayed, you didn’t tell us you were bringing us to meet your family,” Carolyn chides.

“My mother insists you eat lunch with us. She and my sisters have been looking forward to meeting you.” Just then a young woman with flowing black hair enters carrying a tray of small glasses filled with hot tea and fresh mint sprigs, an aromatic drink sweetened with sugar. Sayed smiles, “This is my sister, Zahra.” Setting down the tray, Zahra presents her hand in a Western greeting.

A sudden knock reveals a young boy carrying round loaves of baked bread on his head. As he heads toward the kitchen, Carolyn comments, “I saw boys carrying bread in the medina.”

“In the oldest part of the city, the homes don’t have ovens. So early this morning the boy came for my mother’s dough and took it to the ovens to have it cooked.” As I wonder how the baker remembers whose bread is whose, Sayed reads my mind. “Every household uses a homemade lace cover to identify their dough so they know where to return it.”

The meal ready, Sayed leads into the dining room.

“The boy has perfect timing,” I note as the lad with his now empty tray lets himself out.

“He knows what time we eat,” Sayed explains.

As we enter the dining room, any visions of reclining on a plush rug propped up by pillows is quickly replaced by a large, wooden dining table surrounded by mismatched chairs. “Please sit,” Sayed says pointing to two seats as more of his sisters join us.

The only boy among five sisters, Sayed has a unique position in the family. His three older sisters are married with families, evidenced by small children peeking around a doorway hoping to spot the strangers in their home. With Zahra expected to marry soon, little Fatima has taken over the role of student, learning to cook and run a household from her mother. Of the six, only Sayed has the opportunity for higher education.

Zahra, two years younger than Sayed, speaks English and is the most curious about our lives. Knowing we come from divergent backgrounds, my roommate and I entertain our hosts by describing Carolyn’s life in bustling Chicago while I regale them with tales of things bigger and better in Texas.

Sayed’s mother enters carrying a large platter. Setting it down, she turns to young Fatima who dips a spoonful for each guest and then Sayed before serving each woman according to age starting with Sayed’s mother. The delightful salad is made with fragrant, ripe tomatoes marinated in vinegar and oil topped with olives and parsley. Breaking open a wheel of warm flatbread, I sop the fresh juices and tell Sayed I love his mother’s dough. When the words are translated, the woman beams at me across the table.

After the salad Fatima spoons each of us mounds of fluffy couscous topped with steamed potatoes, carrots and zucchini with chunks of mutton cooked in warm spices and prunes that give each bite a wonderful savory-sweet combination. When I can’t eat another morsel, Fatima puts half of a peeled orange dusted with cinnamon in front of me, a simple and refreshing palate cleanser that’s the perfect endnote to a fabulous feast.

Though Carolyn and I try to help Sayed’s mom with the dishes, we never make it near the kitchen and are soon trailing Sayed again as he knowingly navigates the winding streets across the walled city. Entering a leather shop, we climb the back stairs emerging on the rooftop under a blinding sun. Blinking to let my eyes adjust, Sayed hands us bouquets of fresh mint. “It helps with the smell,” he says, demonstrating how to hold the herbs under our noses.

From this height we have a view of the open pit below where wiry men, leathered from the sun and dressed only in loincloths, wade in huge vats. “Over there is where the hides are dried, cleaned and softened,” Sayed explains pointing to one area surrounded by tall buildings.

The process, still done in the traditional method, uses cow urine and pigeon droppings and despite the mint springs their acrid odor fills my nostrils. “But here in the round vats,” Sayed points directly below us, “that’s where the hides are dyed using natural colorings.” Turmeric for yellow, indigo for blue and poppy for red.

I look out across the rooftops at the spiked minarets jutting out like a forest of trees “Are all those mosques?”

“Yes, we have more than three hundred in the medina.”

Following the tannery pits, Sayed takes us to a carpet factory where we see a group of children working large looms. “My factory feeds hundreds of families,” the owner says. As Omar talks, a small girl carrying a tray brings more mint tea. Handing a glass to each of us Omar explains, “As it is forbidden for Muslims to drink alcohol, we call this Moroccan whiskey.” Smiling, we raise our glasses and sip the sweet, hot brew.

Omar draws up two chairs then unrolls rug after rug in every color – canary yellow, burnt sienna, azure blue. Turning over the carpets he shows the intricate hand-stitching, and after unfurling a particularly large rug explains, “It took four women more than a year to make this. But look at the fine needlework. It’s so detailed one of the seamstresses went blind.” It’s a common tale, we learn, repeated in rug shops across the medina.

The show continues after the tea is gone and the stack of unfurled rugs has reached an impressive height. Though Omar realizes we aren’t in the market to buy his beautiful carpets, his charm and hospitality never waver.

Our next stop is a Berber blanket factory where we learn how each tribe has their own distinct pattern. Sayed then leads to a brass and copper workshop before Carolyn and I get a hands-on demonstration of natural hemp products in a cosmetic shop. Emerging from the artist’s chair, the image in the mirror looks back at me with painted eyes, ruby lips and a red circle between her brows, a symbol of fertility among the Berber tribes, the woman explains.

Once Sayed directs us back through the arched door of the medina, it’s late in the day. Stopping at his favorite fruit stand, he orders a round of banana milk, a subtle concoction sweetened by fresh goat milk. Then we climb a nearby hill to watch the sun set behind a forest of minarets.

Outside the bustle and commotion of the medina, Fez seems quiet and calm. On our hilltop perch we hear soft brays from a parade of medina taxis departing the walled city for the night. But in Morocco, such serenity is short-lived.

Waving goodbye to our wonderful host and new friend, Carolyn and I board the bus for our next stop in this wild country.

To be continued ….

Amazing! You are writing things I’ve never heard and love it. Many thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you! Glad you’re learning something new and enjoying it! 😉

LikeLike