I think everybody has their own way of looking at their lives as some kind of pilgrimage.

– Eric Clapton

Mondoñedo cathedral at daybreak

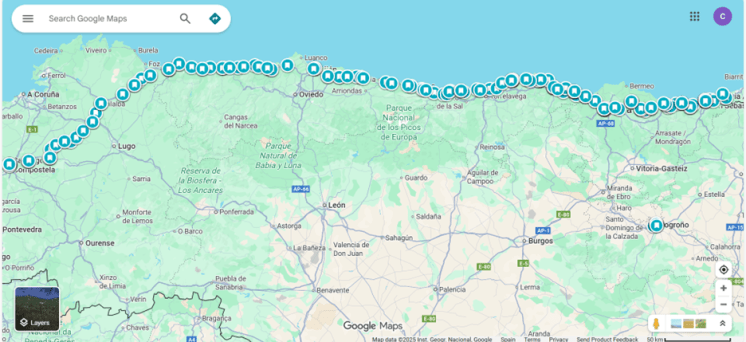

Three weeks ago I finished walking 514 miles from the border of France to Santiago de Compostela. It was quite the journey.

While I still haven’t wrapped my head around the feat – or figured out why I wanted to make the pilgrimage to Santiago’s grave in the first place – I’ve compiled a few observations about the route to entertain armchair travelers and inspire future peregrinos.

1. It’s a long walk.

This may seem obvious to most people, but the truth is the three-inch distance from Irun to Santiago on the globe didn’t look that far.

It is.

While some guides say it can be done in a little more than a month, it took my sister and me 47 days to complete, walking an average of 12 miles a day while adding in a few rest days along the way.

2. The Camino del Norte doesn’t start at the French border.

This was another surprise, one we only learned after walking the first 15 miles from Irun to Pasajes where we met a pilgrim making the journey along the Camino in reverse. After congratulating him on being a day from his destination, he explained that the Camino del Norte doesn’t begin at the border. It begins in Bayonne 35 kilometers inside France.

Historically, Sainte-Marie Cathedral in Bayonne was the gathering place for peregrinos coming from western Europe because it sat at the crossroads of two caminos. From there pilgrims chose the Camino de Baztán across the French and Spanish Pyrenees toward Pamplona meeting up with the Camino Francés or traveled along the coast to Irun and so beginning the Camino del Norte. Today, however modern pilgrims start the journey to Santiago in Irun, Spain.

3. There’s more than one way on the Path of St. James.

Every day pilgrims must choose which Camino to hike. While the main route typically follows an inland course that summits large peaks there’s often an alternate way along a rocky, narrow path hugging the coastline. Or sometimes the yellow arrows send peregrinos on a circuitous route instead of a more direct path through town.

While the main route is always well marked, the alternate route can be confusing. And though it’s nice to have the choice of seaside views versus mountain forests, the options can be annoying for those who simply wants to follow the “one way.”

4. Most churches on the Camino del Norte are closed.

While this trend is happening across Spain it seemed particularly heartbreaking on a pilgrims’ path. Concerns regarding security, lack of staff and rising maintenance costs are the primary issues.

Many villages lack the resources to staff the small churches each day. Others worry about vandalism and theft of valuable items while a shortage of priests and an aging, declining population also play a part in the locked doors of churches along the Camino del Norte.

5. The Camino del Norte follows N-634.

While I thought I was following in the footsteps of medieval pilgrims on the route to Santiago, I quickly discovered the narrow, rocky paths, winding forested trails and steep mountain ascents weren’t the same paths traveled by ancient peregrinos wearing modest wooden shoes and carrying a stick with a bag of their possessions. The paths we walked were a recent addition to the Camino forged for modern, Hoka-wearing hikers carrying 35-liter backpacks using cellphones with GPS. But if there was a route that followed the old Camino del Norte it was National Road 634, also known as the Irun to Santiago de Compostela Highway.

N-634 was built on footpaths once trod by locals to visit neighboring villages, so when some hikes took the rough, uneven goat path involving 500-meter ascents with steep downhills that led to crossing streams on rotting logs, slippery rocks or old bicycle tires, I opted for the road and a more direct route. Because as one fellow pilgrim explained, “They put the road there for a reason. Use it.”

6. In wet, rainy northern Spain giant slugs are real.

Step on one of these and you’ll be cleaning guts off your shoes and pant leg for a week.

Trust me, it ain’t pretty.

7. Northern Spain is filled with eucalyptus forests.

The preferred diet of koalas, eucalyptus are native to Australia. Introduced to Spain in the 19th century by a Galician priest returning from Down Under, these fast-growing trees and prolific pollinators soon spread across northern Spain. With long, thin trunks and peeling bark, the trees transformed rural areas and now provide welcome shade for pilgrims on the Camino.

8. It’s important to keep track of the time and know what day it is.

In Spain lunch (comida) begins at 2 p.m. and lasts until 4 p.m. while dinner (cena) doesn’t begin until 9 at night. So, if you arrive in town looking for a bite at 4 o’clock you’ll find every kitchen closed and most small grocery stores shut for siesta. And if it’s Saturday, those shops likely won’t reopen until Monday.

Weekends mean sharing the path with day hikers and local biking groups. Mornings mean meeting people walking their dogs. Mondays are the day most restaurants give their staff a rest (un día de descanso) while still others close Tuesday and Wednesday. And when tourist season ends in September, many family-run stores and cafés close for a month of vacations. It’s all part of the charm of Spain.

Unless you’re caught with nothing more than the remnants of a three-day old baguette, a can of tuna and wedge of molding cheese between your growling stomach and a good night’s sleep. Only then will you figure out it’s wise to stop whenever you cross a bar for a café solo or your seventeenth bocadillo de tortilla, the ubiquitous potato and egg omelet on a baguette. Because as one pilgrim put it, “On the Camino del Norte you learn to stop where you can since it’s hard to know if you’ll find another.”

9. The Camino del Norte is not for adherents of the keto diet plan.

Speaking of potatoes and bread, they’re the staple foods in Spain’s northern regions. While many take their guests’ health into consideration and depict pictorial images of potential allergens on menus, few dishes go light on the carbs.

Reading a menu in northern Spain felt listening to Benjamin Buford Blue, better known as Bubba from Forrest Gump describe the dishes he could make with shrimp. Except here, shrimp was replaced with carbohydrates. Potato and egg tortilla, paella overflowing with starchy rice, French fries topped with ham and eggs and bocadillos made with fluffy, crusty baguettes. And no healthy seed or whole wheat breads here. Even the simple triangles Spaniards call “sandwich” occasionally filled with vegetables are made on soft, white bread.

Following the Atlantic coast, the Camino del Norte passes through quaint fishing villages offering abundant seafood. But the fresh catch comes with pasta, rice and potatoes or gets served atop a baguette as a pintxo or tapa. The one bright spot is what’s known everywhere as ensalada mixta or mixed salad. Yet even this bowl briming with iceberg lettuce, tomatoes, olives, onions, tinned tuna and one canned asparagus spear only tastes good the first six or seven times. After that, you’ll be ordering the carb-heavy potato tortilla on a baguette with a side of fries.

10. A pilgrimage across Spain means eating pork for a reason.

There’s no escaping pork in Spain.

The country consumes more pork per capita than any other place on the planet. Easy to raise with large litters, pigs are economically efficient animals, and historically every farmstead kept a few around to slaughter for celebrations. During the Reconquista and Spanish Inquisition, Spaniards ate pork to distinguish themselves from Jews and Muslims, demonstrating adherence to Christianity and serving as a public declaration of faith.

After centuries of perfecting their techniques, Spain produces some of the best ham around. Served as chops, sausages and ribs, thickly sliced jamón Ibérico and thinly sliced jamón serrano, in bocadillos (large sandwiches made on baguettes), scrambled eggs, sautéed vegetables and stews, pork is impossible to avoid. And don’t bother asking for meatless options because Spaniards don’t consider pork meat; they consider it an essential ingredient like salt or olive oil. At one restaurant I overheard peregrinos ask for recommendations without meat and listened to the server rattle off a string of dishes containing pork. Because in Spain “meat” means beef.

But after seven weeks on the Camino even the most die-hard pork fans will crave a little chicken.

11. Few places on the Camino del Norte have air conditioning.

Only a handful of the forty-odd hotels we stayed in had air conditioning, but they all had windows to keep us cool at night. That meant we heard a lot of street noise in places like Bilbao, San Sebastian, Gijón and Santander where the towns’ streetsweepers rambled by every few hours (because streets in northern Spain are nothing if not immaculately clean).

In the many small towns and villages, we went to bed listening to dogs barking and geese honking and woke up to crowing roosters. What none of our guidebooks mentioned, however, was the importance of bug spray to keep pesky mosquitoes away. And only at one small pension in Oreña we were offered the comforts of window screens and a ceiling fan.

12. Many Europeans hike the Camino in stages.

Close and easy to get to, many pilgrims from Europe hike the Camino in stages over several months or even years. We met many Spaniards using their holiday time for one, two or even three weeks on the Camino del Norte.

In the tiny town of Roxica I ran into two long-term Camino trekkers. The elderly French women, friends since childhood, met in Spain every year to hike a section of the Camino. And now they were on the final leg of a ten-year pilgrimage to make the long-awaited arrival into Santiago de Compostela.

13. Everyone has a different comfort level for winging it.

Many pilgrims plan to sleep in albergues every night. These bare-bones accommodations offer military-style bunkbeds in large, co-ed spaces with shared bathrooms and communal kitchen for cooking your own meals. Most albergues are first-come, first-serve which means hikers should arrive when they open if they hope to get a bunk. But even then there will likely be a line of peregrinos at the door. What no one wants is to end up like Mary and Elena who walked an extra 5 miles (on top of an already long 13-mile day) to another albergue after the first one was full. And when the second didn’t have beds either, the women sleep on the cold, hard floor.

On the other end of the spectrum many of the U.K. pilgrims were on a package plan, one that had been put together by a desk clerk who somehow determined in advance how far they should walk each day and where to lay their heads at night. I admit it’s comforting to know you have a bed at the end of a hard day, but my sister and I didn’t like yielding control of those decisions to someone we’d never met. Instead, we found booking our accommodations three days in advance the sweet spot to provide flexibility within a working itinerary. The weekends, however, were trickier. With people still vacationing at small coastal towns in September, we needed to snag our preferred pension for Friday and Saturday a minimum of five days out.

14. The Camino del Norte attracts a more mature clientele.

Maybe I’d listened to too many stories about twenty-something peregrinos on a shoestring budget walking the Camino Francés and read too many tales of Camino Romeos wooing girls and moving on to another lass the next night in a new albergue. Or perhaps it was the Camino del Norte’s notoriously difficult terrain featuring more than 10 days of ascents higher than 1,000 feet and the too-long distances between towns.

Most likely it was the fewer accommodations and services catering to pilgrims along the northern route. Because the second oldest path to St. James’ tomb isn’t dominated by budget-friendly albuergues. And their absence leaves many to eat out and stay in higher priced accommodations leading to an older, more affluent group of pilgrims.

15. For many peregrinos, the Camino del Norte isn’t their first pilgrimage.

My sister and I were stunned at how many of our fellow pilgrims were on their second, third or even ninth pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. And there was always someone on the trail who knew of a mythical peregrino working to get their 18th scallop shell tattoo. But if the Camino was a representation of a pilgrim’s spiritual journey with hardships to be encountered and overcome, and the arrival at St. James’ tomb a symbol of the path to salvation and enlightenment, then why do it again?

Like an addiction, peregrinos return again and again to make the trek to Santiago by a new route. While pilgrims of old may have seen the journey as a way to forgiveness and transformation through physical hardship and spiritual focus, modern pilgrims view the trip as an exercise in self-sufficiency and way to commune with fellow hikers while prioritizing nature over technology.

If my informal survey was any indication, most peregrinos hike the Camino Francés on their first trip before returning along the shorter Camino Portugués. Only on their third trip to Santiago do they attempt the arduous, mountain journey on the Camino del Norte. So when the inevitable question came up, our fellow pilgrims were amazed we’d chosen the del Norte to start. “You picked the hardest one for your first Camino,” they said.

I explained that this wasn’t my first Camino. It was my only Camino.

“You’ll see,” many replied. “You’ll feel a pull to come back. Once you’re home, you’ll want to return. It’s the power of the Camino.”

But I don’t have a home. As a white-collar refugee traveling for a living, there’s always a new hill to climb and another destination to discover. While only time will tell if I’ll return to the Camino, for now Robie and I plan to enjoy exploring southern Spain before traveling to Morocco for the winter.

Thanks for tagging along!

Stay tuned for more updates on the Camino as well as ongoing adventures in Spain and Morocco. And if you never want to miss a post, leave your email in the subscribe box and have it delivered right to your inbox.

Great rendition of your pilgrimage. Loved the word pictures. Felt I was on the trail…minus the fatigue, soreness and mosquitoes. Thanks for the ride-along. Amazing trip.

LikeLike

Glad you got to experience it in the best way!

LikeLike

514 miles is no joke, what was the most challenging part of the Camino del Norte for you? 🏃♂️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marcus, your questions always make me stop and think, and I appreciate that.

For me, the hardest part of the Camino del Norte was the first week. While the entire route is notoriously mountainous, the steep climbs every morning in Basque Country were particularly daunting. I was getting used to hiking every day and carrying my backpack which I hadn’t had available during training. My sister and I were trying to find our rhythm since I enjoy solitude in nature while she’s more social. Then there was getting used to Spanish mealtimes. If we wanted to eat something besides tapas or a sandwich, we had to stop and find a restaurant between 2-4 p.m. since most kitchens don’t open before 2 p.m. and many restaurants close from 4-8 p.m., especially in the small towns along the Camino. By the time we reached Cantabria and got acclimated, the daily hiking routine felt completely natural.

LikeLike