The world is a book, and those who don’t travel read only one page.

– St. Augustine

People don’t write books about travel any more.

And why would they? Digital photo albums pop up to remind us of places we’ve been while social media provides a steady stream of other peoples’ selfies in front of exotic backgrounds. In their wake, we’ve shed the adjective laden soliloquies romanticizing a destination or vista, abandoned the tales of trains to distant destinations or cruises around the Mediterranean.

But while a picture may be worth a thousand words, no photograph can express the butterflies you felt planning that safari to Africa, the helplessness after the airline stranded you in Havana without a change of clothes, the frustration as the Shanghai cab drove around in circles, the scent of warm spices from the Strasbourg Christmas market, or the coarse touch of camel hair on your neck when the Egyptian shopkeeper draped a blanket across your shoulder. Despite the very powerful impact of photography, it takes words to evoke the tactile, tangible sensations of a time and a place.

More than photos, books have the power to move us, to make us feel fear, elation, wonder. Growing up, I still remember the books that lived on the shelves by the laundry room filled with my mom’s collection of Harlequin romances and the catalogue of my dad’s management tomes that lined the living room. In other places around the house were titles like Watership Down, Dianetics and Peter Jenkins’ A Walk Across America.

Before the advent of the printing press, Assyrians told their stories on clay tablets, Egyptians on papyrus, Chinese on silk, Greeks on decorative urns, ancient Maya on stone stella, Inca in colorful, knotted strings and Romans on wax tablets. Because telling tales about what lies beyond the horizon is a yearning as old as the thirst to travel. From the Greek Pausanias to the Venetian Marco Polo, from Moroccan ibn Battuta to Englishman Thomas Coryat, books about travel have always been around. They were satirized in Gulliver’s Travels, serialized in The Innocents Abroad and in more recent decades, sent hordes of visitors following the footsteps of an author’s twelve months in Provence and on a journey to renovate a villa under bright Tuscan sunlight. Yet today few people pen travel narratives and publishers rarely print them.

Wikipedia deems travelogues “a special kind of text that [are] sometimes disregarded in the literary world.” But whether it’s a military officer stationed in the desert, missionaries in the jungle, explorers in space, scientists on an Arctic ice shelf, pilgrims on parade, or migrants adapting to a new culture, each of us has a unique travel story. Even writers who gained fame (or notoriety) from other literary works often wrote about their travels, Charles Dickens, D. H. Lawrence, John Steinbeck, Rudyard Kipling, James Michener, Ernest Hemingway and Mark Twain.

Notice anything about that list? Even today nearly all published travel writers are men. It’s simply unthinkable for a woman to leave her husband and kids and go on walkabout. Yet no one bats an eye when Bill Bryson deserts his wife and three young kids to drive across Australia or Paul Theroux leaves his wife and sons on a rainy day in London for a rail trip across Asia. Years after I read Theroux’s The Great Railway Bazaar I secretly smiled when I learned that during his absence his wife took a lover. As the author admitted in Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, he set out for Siberia after ignoring his wife’s pleas not to abandon her with their children.

So, why do men get to go on an adventure and women can’t?

In her book, Women were also travelers, French writer Lucie Azema notes that historically almost all published travel writing is penned by men giving the genre an imbalanced, colonial, misogynistic worldview. Azema further asserts that the few, successful, long-distance female travel authors have been rendered invisible. After all, who’s heard of Ella Maillart, Annemarie Schwarzenbach or Isabelle Eberhardt? Even a current Google search for travel blogs spit out a list consisting of nothing but male names.

Go figure.

While a few fresh travel narratives have been penned by women, notably Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, both authors’ journeys emanated from gut-wrenching divorces and lend credence to the trope of broken females trying to atone for being alone as if we still live in an age where divorcées are shunned. Yet which publisher would have told Peter Mayle he needed the drama of a failed relationship for readers to comprehend A Year in Provence? Or said to J. Maarten Troost in Sex Lives of Cannibals that he had to have a soul sucking divorce to explain the two years he spent in the far reaches of the Pacific? Even at the end of The Great Railway Bazaar Paul Theroux never hints that his marriage is falling apart despite returning home to find another man comfortably ensconced at the breakfast table wearing the author’s bathrobe.

Then again, maybe I’m just cynical. Or perhaps I’m sick of rejection letters. That is, when anyone bothers to respond to my queries at all.

Still, I love the weaving together of genres that combine memoir, nonfiction and the occasional creative license to tell a story that’s exotic, strange, sometimes uplifting, often hilarious and always adventurous. Because truth really is stranger than fiction. And for that reason, I’m making it my mission to bring the travel narrative back to life. To liberate books (whether digitally or in print) that evoke images of distant spaces and bygone days and tell the tales of authentic people in existent places.

Sadly though, my efforts may be too late. Not long after I announced this undertaking, I made a trip to my local mega used bookstore to buy an armload of travel narratives. As I stood inside the sprawling 54,000 square foot warehouse, I noted signs for classic novels and science fiction fantasy, mystery and action adventure, history and current events, true crime and cookbooks galore, philosophy and religious studies, self-help and do-it-yourself projects. But I had to ask an employee for assistance locating the three lonely bookcases in the far back corner of the store where travel narratives went to die.

The shelves were in disarray and the books looked as though they hadn’t been organized in months despite the category’s location next to the frequently used employee breakroom. And I know from experience that the breakroom is frequently used because every time one of the worker bees came in or out, I had to get out of their way. It was a sorry state for a formerly beloved category that gave armchair travelers the opportunity to dream. Yet despite their forlorn condition, I left the store weighted down with books.

Over the years I’ve read my fair share of travelogues, but until this I’d never attempted a study of the field. And since I began this project while I was still a worker bee myself, I needed a simple format for critiquing the tales. So in this ongoing series I’ll recap the narrative and ask four questions:

- Did I enjoy reading it?

- Did I learn something new?

- Does the journey make me want to pack my bags?

- Does the author inspire me in other ways?

Then you decide whether to read it.

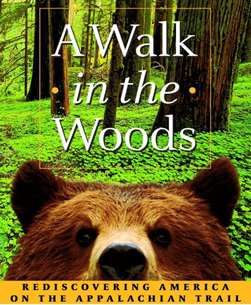

For this debut post, I picked a famous writer and one of his better-known books. Perhaps you’ve seen the movie (I haven’t) and so don’t feel the need to read the book. But everyone knows that the movie is never as good as its book. Besides, who can resist the cover of a furry-headed, wet-nosed, fuzzy-eared bear staring at you with inquisitive eyes and a slightly hungry look? I offer for your consideration Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail.

Setting off on a 2,100-mile hike on the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine, the American writer recently returned to the States after two decades in England, hopes the excursion will get his middle-aged dad bod in shape, reacquaint him with the land of his birth, and let him boast at parties about defecating in the woods.

While most people would settle for a gym membership, a Sunday drive to some distant corner of their state and using a port-o-potty at an outdoor concert, Bryson also seemingly wants to see the American wilderness. So despite warnings about bears, rattlesnakes, hillbillies, parasitic worms, lightning strikes, fire ants, Lyme disease, hantaviruses and murderers, he boldly charges ahead. The only problem is that Bill doesn’t want to make the trek solo, and no one’s senseless enough to spend months alone with him in the wilderness. (Can you blame them, really?) No one except his old travel buddy and slightly crazy friend, Stephen Katz.

As Bryson points out, this is his same friend from high school who traveled with Bill through Europe in the 1970s, a story detailed in another one of Bryson’s books, Neither Here nor There: Travels in Europe (to be reviewed in this series at a later date once the reviewer has a chance to read it). And while I can well imagine a twenty-something, beer guzzling Katz in Europe, when we meet him in A Walk in the Woods, he’s a recovering alcoholic. Alone in the woods with Bryson.

What could possibly go wrong?

Starting in northern Georgia, the pair set off with their forty-something, out-of-shape physiques and overstuffed backpacks laden with camping equipment and candy. Each morning they begin walking and only stop when it’s getting too dark to continue. As the author relates, even he finds the scenery tiresome with trees to his left, forests to his right, a jungle he just walked through and more of the same ahead. For anyone looking for a mind-numbing routine to clear their heads, the Appalachian Trail seems the place to go, and Bryson shares his wit and snobbery with every step. While some online reviewers found his style obnoxious, overbearing and pompous, I didn’t. But I also never forgot that Bryson just spent twenty years in England because despite having been raised in Des Moines, the Britishness practically oozes from his pores.

After two months and a 250-mile jaunt in a rental car, Bryson and Katz reach the north end of Shenandoah National Park and part ways, each returning to their respective home. And this is where the book loses me. Not because I thought Bryson and Katz needed to hike every mile of trail, but because their break literally breaks the continuity of the prose. When he picks back up again later, Bryson makes short, convenient day-hikes alone without his stalwart companion, and the reading suffers. Because the best travelogues aren’t about the trail or a destination. They’re about the people we take with us – literally or metaphorically – and the ones we meet along the way. But left to his own company, Bryson’s walks lacked the humor of waiting for Katz to saunter into camp at day’s end exhausted and angry.

Months after reading A Walk in the Woods, I read an interview where Bryson admitted he found the book hard to write because there wasn’t anything particularly eventful about walking, an act he described as “an exceedingly repetitious experience.” He further explained how he’d been forced to fictionalize some of Katz’s behavior since the man was severely depressed during their trek. But instead of writing about what a huge downer Katz was, Bryson portrayed his friend as angry, mad at the world about life and particularly peeved at the Appalachian Trail and the reason he was on it, Bryson.

So, how’d the book do?

- Did I enjoy reading it? I enjoyed the first two-thirds of the book which was funny and well-written. But I could have skipped the latter third. It wasn’t that it was bad, it just lost continuity with the first part despite the closure it brought to the journey.

- Did I learn something new? I learned a lot about a region of our country that’s often overlooked. And about Bryson’s paranoia regarding anything and everything that had the potential to kill him on the trail.

- Does the journey make me want to pack my bags? There are two things you will learn in future posts: I lived in Appalachia for a year when I was young and already know it’s acutely unlike any other region of this country; and I recently invited my sister to trek the Camino de Santiago with me. So, did Bryson’s book make me want to set out on the Appalachian Trail anytime soon? Alas, no. But I am more than happy to sit in my favorite reading chair and let Bryson and Katz do the hiking for me.

- Does the author inspire me in other ways? A Walk in the Woods certainly brought home the fact that I am not in shape to hike the Camino. So, it’s inspired me to get out of my reading chair before I keel over from a heart attack in Spain. And like any good travel narrative, it inspires me to write.

I hope you enjoy Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods even if you only put it on your list of movies to watch. As of this writing, it’s currently available for free on Tubi, Pluto TV, The Roku Channel, Peacock, Sling TV, PLEX and Amazon Prime or via subscription on Hulu and Netflix. Or you can rent it on Google Play Movie, Apple TV, YouTube and Fandango at Home. Now excuse me while I press play and watch the unlikely pair that is Robert Redford and Nick Nolte. (Sorry, I don’t do movie reviews.)

If you read A Walk in the Woods, I’d love to hear what you think. Leave a comment below for everyone to see or click Contact and send me your two cents. After all, thanks to social media, we’re all critics now.