What do I do here

I don’t know

I just wanna walk straight ahead – Schengen Shuffle by Hét Hat Club

Being homeless wasn’t going to be easy.

Picking up and moving every ninety days sounded like fun. But would it be? Really?

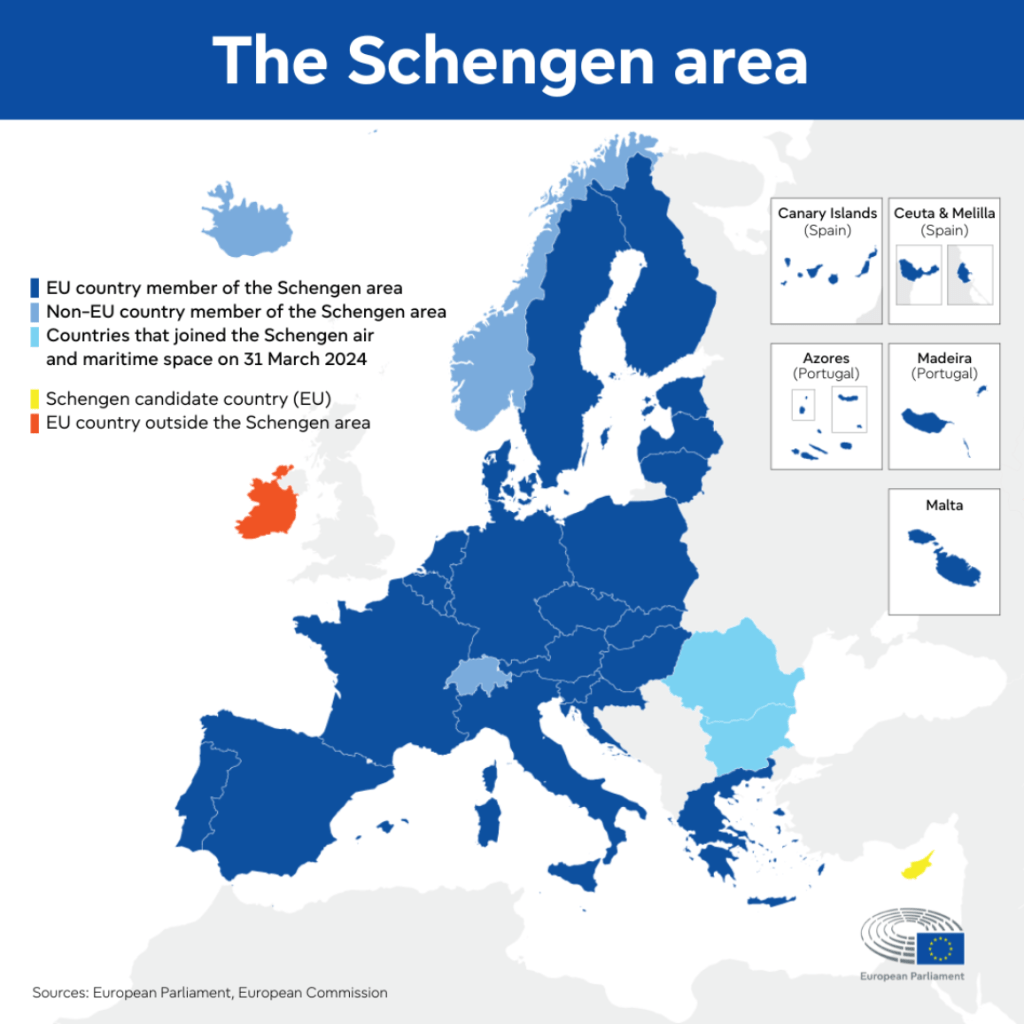

Especially since Robie and I couldn’t amble about Europe on a leisurely Grand Tour spending a year in Italy, six months in Greece and on the way back to London stopping off in Bohemia for another half-year. Because what began in 1985 with five European countries in the tiny village of Schengen, Luxembourg has grown to encompass 29 nations and give 425 million people unlimited access across the region.

Before the Schengen Agreement, crossing borders was annoying but mostly uneventful. On my first trip to Europe immigration officials boarded trains and strolled down the long line of railcars stamping passports followed closely by customs officers asking if we had anything to declare. But like governments everywhere, some places liked to shake things up. In Spain we were required to disembark and queue up for processing at the tiny border stations. And when the ferry docked from Greece, Italian Customs ordered us to drop our luggage in one long line on the pier as they led a drug-sniffing German Shepherd over the top.

As a college student venturing into Eastern Europe at a time when the Berlin Wall was still very much intact, border crossings were a big deal. I was, after all, a dreaded capitalist and potential revolutionary. At Checkpoint Charlie and along the borders of Hungary, Romania and the former Yugoslavia, the process was painstakingly slow and always tense. I was forced to exchange a minimum amount of U.S. dollars into the local currency at inflated rates, required to obtain a special tourist visa and compelled to sit through round after round of redundant checks by intimidating, Soviet-trained, East German officers.

Ever wonder why Cold War baddies always appear angry? You would be too if you lived under one of the world’s most repressive regimes, lacked access to necessities like food or warm clothes and worked within sight of the free-flowing abundance and neon lights of West Berlin. And if you had the chance to make things difficult for rich Westerners, you’d consider it a perk of the job. Because in your line of work a foul up didn’t just cost your life, it also sent everyone in your family to a Siberian gulag.

Fortunately, those days are long gone thanks to the fall of the Berlin Wall. And now with the Schengen Agreement, tourists and Europeans alike have the freedom to cross the continent’s internal borders without passport checks.

Foreign visitors landing today at Amsterdam’s Schiphol International Airport on the way to Milan undergo Customs and Immigration in the Netherlands but not again Italy. If they board a train in Zurich and travel to Munich and then on to Strasbourg, they aren’t met by officials checking papers as the train glides through Switzerland, Germany and then France. Because each of those countries are members of the Schengen accords. But while Schengen makes moving around Europe easier for everyone, for those of us without EU passports, our time spent within the continent is severely curtailed.

In the past every border crossing came with a new three-month tourist visa. If Robie and I landed in Vienna, we could visit Mozart’s birthplace, watch Lipizzaner horse dancing and yodel from atop Austrian Alps for ninety days. When our visas ran out, we could cross into Czechia and find another welcome mat unfurled for three more months. If we chose, we could spend an entire year eating Sacher torte in the Viennese winter, toasting steins of Budvar in the Prague springtime, stroll the narrow streets of Slovakia’s medieval Bratislava in summer and cruise the Danube in Budapest in the fall.

Not anymore.

Today each of those country’s tourist visas are subsumed by Schengen. And they’re not alone.

The list of Schengen countries is long. Though the original open-border treaty operated independently of the European Union, in 1999 the accord was incorporated into the union’s laws and is now one of the core requirements for joining the EU under “free movement of [the] people” making it valid in all European Union members except Cyprus and Ireland. And with the adoption of the Schengen treaty by four non-EU states, the affected list stretches further to include Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and even little Lichtenstein.

Most recently, in March 2024 Romania and Bulgaria were added to Schengen leaving only a handful of European countries outside the zone. In addition to Belarus, Armenia, Cyprus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Azerbaijan, Montenegro, Albania, Serbia, Belarus, North Macedonia, Georgia, Moldova, Russia, Kosovo, Ireland, the U.K., Türkiye and war-torn Ukraine, Robie and I could hide out in the microstates of Andorra, San Marino and the Vatican, countries that aren’t formally part of the Schengen Agreement but are completely surrounded by treaty members.

If that list sounds restrictive, it’s only half the problem.

While the Schengen Agreement allows freedom of movement for its member citizens, for foreign visitors like us, the accords limit the amount of time Robie and I can spend inside the treaty zone to three months. And once those ninety days are up, it’s not simply a matter of crossing a border outside the region for a day or three before returning. Within any rolling six months, we would only be allowed in the Schengen zone for ninety days. Total.

It meant that if we decided to roam around Poland, Portugal and Croatia, at the end of three months we’d need to spend the next ninety days outside the Schengen zone before stepping foot back in.

For Americans, the best way to think of all this is to consider most of Europe’s countries as states because that’s essentially what the Schengen Agreement created. Visitors to the U.S. might want to spend a year traveling cross-country, but with a 90-day tourist visa they’d have to plan their time wisely if they hoped to catch a show on Broadway, wander the halls of the Smithsonian, see Mickey Mouse in Orlando, dance the night away on Miami Beach, take a selfie at Southfork, ride donkeys in the Grand Canyon, ski the Rockies, flyfish in Montana, play blackjack in Vegas and shop on Rodeo Drive.

But if traveling from Norway through Sweden to Finland is no different than a road trip through Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, then we can continue the analogy by considering the non-Schengen members in Europe the equivalent of Canada or Mexico, separate and outside the 90-days-out-of-180 limit.

But even there, things vary. While most countries still grant visitors three-month tourist visas, in Great Britain Americans are allowed six months, and in Albania we’re able to stay a full year. So, as Robie and I looked to hopscotch in and out of the Schengen zone, we knew we’d rely heavily on these outliers. To complicate matters further, I’d committed to walking the Camino de Santiago with my sister in the fall of 2025, eating up another ninety days inside the Schengen zone as we attempted to hike across northern Spain.

But before any of that could happen, Robie and I had work to do. While I continued working, the newly retired Robie labored to get the house ready to sell. As he created a monthly budget and researched apartments where we could stay, I began training for the Camino.

And together we wondered what to do with all the stuff we’d accumulated over the years.

very interesting, helpful and educational – can’t wait for the story to continue!

LikeLiked by 1 person