The people you surround yourself with influence your behaviors, so choose friends who have healthy habits. – Dan Buettner

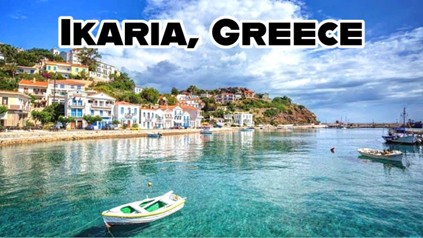

Robie and I didn’t set out to age in reverse, on Ikaria it just happened.

Ikaria is a blue zone – one of only five in the world – where people regularly live longer than average.

The term, coined by National Geographic Fellow and journalist Dan Buettner, originated while researching centenarians in Okinawa, once called the land of immortals where inhabitants have fewer incidences of cancer, heart disease and dementia, and women live longer than anywhere else on Earth. After Okinawa, Dan and his colleagues set out to identify other places where people often lived to ripe old age like the cluster of villages in Sardinia whose isolated geography forces residents into a healthy lifestyle that includes hunting, fishing and harvesting their own food.

Along the Nicoya Peninsula south of Nicaragua, descendants of the Chorotega tribe in Costa Rica live in multigenerational homes, consume meals featuring the “three sisters,” squash, beans and corn, and drink water containing the country’s highest concentration of calcium. In Lomo Linda, California Seventh-day Adventists take a break from the rigors of modern life to focus on God, family and nature. And by observing the Sabbath for a day each week, they relieve stress, strengthen social networks and find time to exercise. Plus, since Adventists eat meat sparingly, they have lower blood pressure, reduced cholesterol and fewer cardiovascular issues.

And on an island in the South Aegean, Ikarians fast regularly for Greek holidays, take naps, drink wild herbal tea and frequently live into their 90s.

In their research Buettner and his team identified nine habits of the oldest living humans:

- They move naturally. Whether it’s tending their garden or walking to visit friends, exercise is built-in to their everyday lives.

- They have less stress. While we all have cares and worries, people in Blue Zones have cultural mechanisms to help them cope. Okinawans take time to remember their ancestors, Adventists observe the Sabbath, Ikarians take naps, and Sardinians enjoy happy hours with neighbors.

- In Blue Zones people eat less. Most consume their main meal in the afternoon. On Okinawa, a 2,500-year-old Confucian mantra said before mealtime reminds them to stop eating when their stomachs are 80% full.

- Meals in Blue Zones are plant centric. Meat – usually lean pork – is consumed four or five times a month and then only in small quantities.

- They drink wine. Except for Seventh-day Adventists who abstain from alcohol, people in other Blue Zones drink regularly with friends since research shows moderate drinkers outlive non-drinkers.

- People in Blue Zones put family first. They commit to a life partner, keep aging parents and grandparents nearby, and make time to enjoy their children and loved ones.

- Blue Zones have “tribes.” Researchers know habits are contagious, whether negative ones that lead to smoking, obesity and loneliness or healthy habits like exercising, eating less and socializing. On Okinawa, women create moais, a network of five friends who commit to helping each other for life.

- They have faith. In Blue Zones the longest-lived members of the community have religious beliefs and belong to a faith-based community.

- They have a purpose. Blue Zones residents have what Okinawans refer to as ikigai and Costa Ricans call plan de vida, both loosely translating to “the reason I wake up in the morning.” Or as the plaque my dad had hanging in the hall when we were kids said in big, bold letters, “When you wake up, get up! When you get up, do something!”

On Ikaria, locals eat the strictest version of the Mediterranean diet and have the fewest cases of dementia anywhere in the world. Along with fruits, vegetables, whole grains and beans, they consume foraged greens like wild mustard, chicory and fennel with ten times the artery scrubbing antioxidants as red wine.

A typical breakfast consists of a spoonful of raw honey or extra virgin olive oil, goat’s milk cheese, olives and an ancient porridge called tarhana, a dried mix made from flour, yogurt and groats giving them high-quality protein, complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber and minerals like magnesium, iron and zinc. Ikarians drink wild herb tea that grows on the steep mountainside and reduces blood pressure, rids sodium from the kidneys and helps keep arteries flowing.

On the island locals grow much of their own food. People in mountain villages tend orchards filled with olive, orange and lemon trees. They raise chickens, sheep and goats to make a local stew considered a delicacy. In town, patios are laden with pots filled with peppers, eggplant and tomatoes. They harvest figs and tangerines, and forage for wild oregano, rosemary and sage that grows between the craggy rocks, something Robie and I used to add fresh flavor to homecooked meals.

Alongside our neighbors, we lingered at our favorite café over small cups of strong Greek coffee and enjoyed pastries made with warm, unsalted goat cheese. We sat along the promenade with friends enjoying Ikarian wine made in the traditional way with high levels of antioxidants. And we ate fish regularly.

On Ikaria, calamari’s on every menu alongside sardines, shrimp, octopus, smelt and “Greek French fries,” fried anchovies. When we ordered fish at a small restaurant in Evdilos, the owner left to retrieve the catch of the day from a local fisherman.

We ate sweets made with fresh goat cheese and unpasteurized Ikarian honey supercharged with anti-cancer compounds in nut-filled baklava and loukoumades, little Greek donut holes soaked in honey. And since dining out always came with a complimentary dessert, we enjoyed dried figs in honey, Turkish semolina cake dripping with golden goodness and cups of thick, luscious goat yogurt drizzled with honey that tasted better than ice cream.

Around the island, natural hot springs offer therapeutic baths in radioactive water thought to be good for respiratory ailments, skin conditions, sciatica, indigestion, fatigue, gout, rheumatoid arthritis and lower back pain. And in Therma, a town named for their hot springs, the tap water is said to be good for stomach issues, kidney and liver function.

But the thing Robie and I noticed most about staying in a Blue Zone was how many old people there are.

Grey-haired people are everywhere on Ikaria. Swimming laps in the cold, blue Mediterranean, strolling through the town square, bathing in the thermal hot springs. They line the grocery aisles, patronize the restaurants and cafés, and bask on park benches.

And they’re active. Every morning from our balcony, Robie and I watched two old ladies finish their morning walk with a dip in the therapeutic spa. On our route to town, we regularly greeted an old blind man sweeping his front porch and another elderly man herding his ever-wayward sheep. In the mountains we passed old women tending gardens, feeding goats and chickens, and preparing for the olive harvest. And a few days after arriving we attended Therma’s annual panagyria, an all-night community party where long after we headed to bed elderly locals danced, sang and then danced some more.

On Ikaria everyone fishes. In calm weather tiny fishing boats dot the sea, kids with poles line the port, snorkelers go in search of squid and octopus, and in Therma one woman threw bread into the water and dangled a line every day.

On a mountainous island, every excursion means an inevitable climb. For Robie and me, a trip to the market involved a half-hour walk that began by climbing 163 steps from the beach to a hill behind the town offering stunning views of Therma. Reversing the ascent near the capital, we repeated the hike laden with goat milk, yogurt, fruits, veggies, cheese, dried beans, and Ikarian herbal tea and honey.

Then following naptime and a soak in the thermal baths, Robie and I felt better, younger and sprightlier than we had in years.